Ghislaine Maxwell, Elizabeth Holmes, and Ann Freedman. What do these three women have in common, besides being the dishonorable stars of their respective Netflix specials? They are the single public punching bags for schemes carried out by a number of perpetrators.

As an imperfect woman myself, I am not one to consider all women faultless. These three women hold guilt for their contribution to conspiracies of various horrors. However, it is interesting to examine how these women became the faces of a collective outrage on which the faults of all contributing men were— and still are— placed. In this article, I will cover the crimes of Maxwell, Holmes, and Freedman and the aftermaths they experienced, in which each landed as the front and center fall guy. Together, their stories can illuminate the inherent misogyny in our everyday lives, founded in historical and mythological stories.

A woman acting as the scapegoat for crimes against humanity is not new. Historically, female figures have been placed at the forefront of persecution and public backlash for their involvements, whether active or passive, in wrongdoings beyond their control. Think of Eve in the Genesis creation narrative; in this story, humanity was deemed innocent until Eve yielded to the Garden of Eden’s evil serpent, at which point God forced upon His creations the punishments we now know as childbirth and necessity of labor. Eve the woman— not Satan the seductive snake— is often pegged as the reason for man’s tragic disposition. Think too of how we utilize the term “Mother Nature” when speaking of storms and natural disasters, relating the deaths and irreparable destruction caused by nature’s ways with womankind.

Another example of a woman taking on an unjust extent of blame can be found in the Greek mythological figure, Helen of Troy. In many depictions, Helen and her sister Clytemnestra are considered the villains of the lengthy Trojan War and its aftereffects; Helen’s leaving her husband caused the war, and the unfaithful Clytemnestra murdered her own husband, Agamemnon, to avenge her daughter’s death. As Darah Vann puts it in her article “Helen of Troy: Unwomanly in Her Sexuality,” both women “[stepped] outside of prescribed roles” of wives at the time by engaging in extramarital affairs, leading to their actions being connected with the greatest offense, murder. In Helen’s case, of warring men, and in Clytemnestra’s, of said husband.

The critical depictions of these sisters are easily considered fair because of each’s crimes. It is bizarre, though, to think that the Trojan War is considered the fault of Helen of Troy, that promiscuous woman, when the greedy men of Sparta incited it. In addition, though Clytemnestra is often remembered as the sole murderer of Agamemnon, in reality, she was aided by her lover Aegisthus, an often forgotten fragment of the story. Yet again, another distorted historical example of placing blame on the culpable woman in a given wrongdoing before acknowledging the many offenses by men standing behind or, in actuality, in front of her.

Understanding this history of displaced blame will allow us to properly assess the current perception and treatment of guilty women. On that note, let’s first discuss the most prominent female scapegoat of today: Ghislaine Maxwell. Maxwell is a British socialite who coaxed underage girls to be sexually abused by her companion, wealthy American businessman Jeffrey Epstein, and his influential cohort, including powerful businessmen, British royalty, and President Bill Clinton. After being exposed and convicted for his heinous crimes, Epstein committed suicide in his jail cell, a tragic event for the many victims who hoped to find justice or peace in Epstein’s punishment. Meanwhile, Maxwell found herself charged with six counts related to sex crimes and the remaining living, known figure of the scheme on whom the public could take its anger out.

Maxwell was rightfully found guilty on five of these six counts. I do not bring up her story in an attempt to absolve her of her responsibility in this scheme as I believe she is a very culpable, evil woman indeed. Still, allow me to highlight that Maxwell’s luring was for the purpose of engaging underage girls in sexual conduct with powerful men. Men who, except for a few, have remained quietly unblamed. Should this woman, though no doubt playing a grotesque part in the Epstein scandal, take the entirety of the fall for the dozens of disgusting men who sexually assaulted the victims of her disgusting coercion? We, as a society prone to dishing the full extent of our anger onto a lone— often female— perpetrator, must seek justice for the trafficking survivors through the investigation and indictment of men who reaped the perverted benefits of Maxwell’s connivances and see none of the consequences.

Next, let’s cover the public downfall of the founder of failed Medtech startup Theranos, Elizabeth Holmes. Since its founding in 2003, Theranos received praise across Silicon Valley and beyond for its ability to conduct numerous blood tests from a single finger’s droplet of blood. In addition, the company was celebrated for being founded by a woman, a sparkling diamond in the bleak, male-dominated mine of Silicon Valley. Holmes became an inspiration to female entrepreneurs everywhere, a case study of concurrent beauty, brains, and business prowess.

Soon, however, Holmes’ company would serve as a reminder to never believe what is too good to be true. In March 2018, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission charged Theranos, Holmes, and former president Ramesh Balwani for their false claims about the blood tests’ accuracy. Theranos’s product proved fraudulent, and Holmes was revealed to be nothing more than an aspiring billionaire without a substantive medical background.

As the face and founder of Theranos, it is no wonder that Holmes took the public and legal fall for the failure and crimes of her false company. However, it is interesting to observe that the femaleness once central to her company’s branding, deemed admirable to outsiders and therefore significantly contributing to Theranos’s success, largely contributed to the company’s downfall. As Theranos dissolved, critics rushed to scorn Holmes’ faked deep voice and her investors’ interests in her person— her blonde hair, blue eyes, and captivating nature— rather than her fraudulent mission. The public often disregarded the legitimate offenses Holmes committed in favor of picking apart her persona and, specifically, her womanhood. In the end, the exact quality of femininity that facilitated the rise of Holmes’ company as Silicon Valley grasped at straws for a female success story was twisted into not only a joke, but also a point that the public could gratifyingly scrutinize under the presumption of fair criticism of Theranos and its creator.

Evaluating how we react to women on opposite sides of public favor illuminates our collective tendency to resort to diminishing women when it’s deemed “safe.” As Holmes achieved unprecedented success, people praised her, considering her an inspiration. When Holmes was exposed to be a fraud, people, in the comfort of general dislike for the CEO, openly disdained her deep voice, claiming her a seductress using her looks to advance Theranos. Criticism founded in misogyny is not valid criticism. Thus, when regarding a given woman who has sincerely wronged others through her faults, we must meet the woman’s deeds with criticism equal to their extent rather than slander her for qualities merely relating to her femininity.

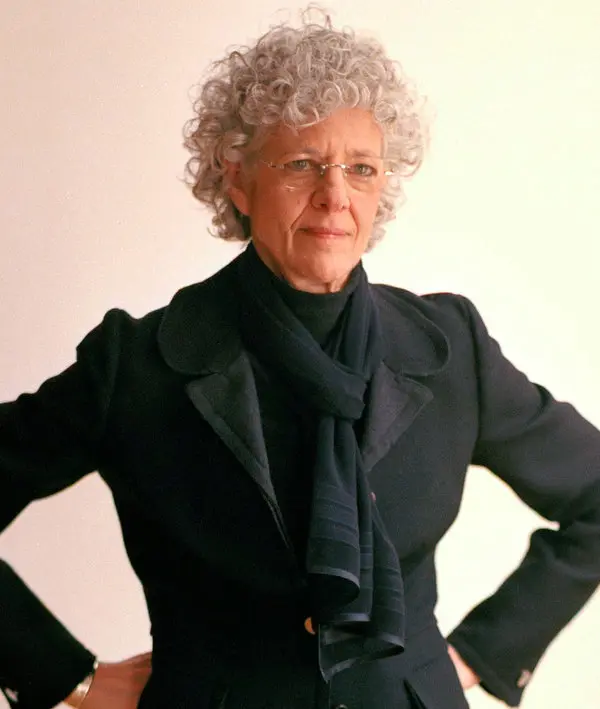

Finally, allow me to introduce the fraudulent art dealer and antagonist of documentary Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art, Ann Freedman. Freedman was once the director of the Knoedler Gallery in New York City, owned by wealthy businessman Michael Hammer. When disreputable Glafira Rosales began bringing Freedman what she claimed were lost Mark Rothko paintings, and later those by other Abstract Expressionists, Freedman bought the paintings for cheap prices and displayed them for potential buyers. Over the course of Freedman’s buyer-seller relationship with Rosales, the Knoedler Gallery sold over 30 fraudulent paintings. Soon, these works sparked interest in the art community for their ambiguous origins. After continued investigation, in 2013, Rosales admitted that the works she brought to Knoedler were fake, painted not by famed artists of the 1940s New York Abstract Expressionism movement but by a man named Pei-Shen Qian in Queens, who fled the U.S. upon hearing of the investigation into his fraudulent works.

Of the three women discussed here, Freedman objectively did the least amount of damage, harming only the rich people gullible enough to buy fake paintings from her gallery. Okay, I’m being harsh. Of course, according to consumer protection laws, consumers should not be expected to question the claims of a seller. And one case of fraudulent art brings into question the validity of art everywhere and therefore our societal structure. So, yes, if Freedman knew that the Rothkos and Pollocks brought to her by Rosales were fakes and willingly sold them to collectors, her behavior should certainly be considered conniving.

I do not think it’s outrageous to suspect that, considering the financial incentives to do so, Freedman may have knowingly sold fakes. I think it’s more outrageous that, despite the many individuals who signed off on the paintings’ authenticity and the boss who not only OK’d but encouraged every transaction, we continue to consider Freedman the principal villain of the Knoedler Gallery scandal. While owner Hammer, Rosales’s mastermind boyfriend Jose Carlos Diaz, and the fraudulent painter himself Qian walk free of intense public scrutiny or legal charges, Freedman remains the subject of the art world’s contempt. In addition, the only figure involved in the scandal to receive a criminal indictment was woman Rosales.

Though examining the downfalls of real-life villainesses can be fascinating, it is important for us, as beings prone to misogyny according to our cultural framework, to remain conscious of our attitude towards women when discussing their crimes. Maxwell, Holmes, and Freedman provide interesting individual cases for the question of whether we place an unnecessary amount of blame on women relative to men participating in crimes of the same nature.

However, the analysis of our general perspective on female guilt should not stop at three famous and wealthy culpable women. I encourage you to frequently question your own attitude towards women by assessing your judgment of female perpetrators. If you see a woman at your workplace get blamed for her superior’s ignorance, for example, or a female student scrutinized for a minute mistake, ask yourself: are we adequately addressing her misdeeds or unnecessarily inflating the extent of her involvement while dismissing contributing men’s roles?

Categories: Culture