Copper is an incredibly important part of the societal transition from fossil fuels, potentially even more important than lithium, since experts like Michael Webber agree that battery manufacturers can skirt lithium needs far more easily than copper needs. There is no material that conducts energy with such a high efficiency quite like copper does. Renewables like electric vehicles, wind turbines, and solar panels all use far more copper than any fossil fuel counterpart. These technological changes are very desirable, but to what extent should we go to obtain copper? After all, we need more copper if we are going to be a leader in the green revolution, yet we lag behind many other countries in domestic copper production. In the Ninth Circuit case, Apache Stronghold v. United States (March 2024), the government decided that turning an active Native American religious site into a crater was not in conflict with freedom of religion and is, in fact, beneficial for job creation and flinging the U.S. into a green future.

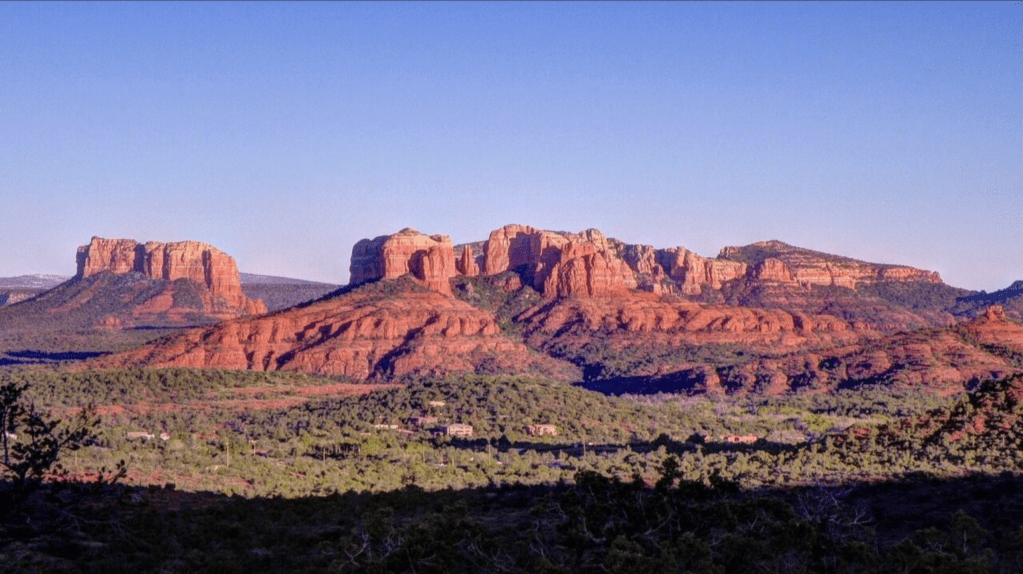

While this legal issue of resource extraction on Native lands is not unique, Apache Stronghold’s attempt to use religion as a method of regaining a sliver of tribal sovereignty is. The mining site in question is located on the religious site known as Chí’chil Biłdagoteel on the Oak Flat reservation in Arizona, and the estimated crater size would be about 2 miles wide and 1000 feet deep. The destruction of the site would directly interfere with a crucial coming-of-age ceremony for girls who must gather local vegetation in the area that directly connects them to the spirit of the Creator (housed within Chí’chil Biłdagoteel) at a crucial moment in their life. The U.S. Forest Service has jurisdiction over Oak Flat and has long protected the reservation until 2014, when senators from Arizona snuck in a bill at the end of a must-pass defense bill that codified the process for the trade of lands in Oak Flat to Resolution Copper in exchange for some of Resolution Copper’s land. Resolution Copper is a joint venture between Rio Tinto and BHP Group that was created in response to geological reports espousing a massive copper deposit of 1.7 billion metric tons in the area. They portray themselves as the harbinger of the copper-fueled green revolution within the U.S. and as a positive force for the local economy. However, not only is the Aluminum Corporation of China the largest stakeholder in Rio Tinto, but China is responsible for 57% of their sales last year. There is a high likelihood that much of the copper would leave the U.S. because of this. Additionally, the ecological impact of turning the land into a toxic soon-to-be sinkhole would be more of a drain on the economy than the very temporary creation of mining jobs. Because of long-held legal precedent dating back to shortly after the American Revolution, plenary power allows the federal government to have authority and power over the Native American tribes, meaning that the Apaches of Oak Flat could do nearly nothing in the face of the hidden clause within the defense bill.

However, precedent clearly put forth in Yoder v. Wisconsin and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) were extremely useful to the Apaches, who went to court in an effort to show that destroying a religious site impeded their ability to practice their religion as promised in the First Amendment. When the case made it to the 9th Circuit Court, the main area of contention was whether turning a religious site into a crater would place a “substantial burden” upon a faith’s practitioners, in which, afterwards, a nonsensical conclusion was reached by redefining the concept of “substantial burden.” By roping in outdated precedent from Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association, the 9th Circuit established that since the disposition of federal lands was involved in a case like this, the destruction of religious sites was allowed. The 9th Circuit said that decimating Chí’chil Biłdagoteel would not impede the Apaches from following their religion, so the RFRA was still upheld (Apache Stronghold v. United States). Naturally, with a decision as backwards as this one, the Apaches attempted to appeal to the SCOTUS, but they were denied the petition for a writ of certiorari (which is when a higher court reviews the decision of a lower court). The only reason Resolution Copper did not begin digging in August of this year was because of a temporary injunction passed for the parties involved.As Justice Gorsuch points out in his dissenting opinion on the petition, this has the potential to be detrimental to the religious freedom of any church, Native “protected” religious sites, or places of worship on federal land. Especially since there is no unified federal database of all the sacred sites under federal control, the impact of this case on non-Natives and Natives alike is frighteningly unknown. Under the precedents created, the federal government has the power to prevent worship to the extent that it can sell land to private companies and bulldoze it all. This case is just one example of the many ways that courts hostile to Native land rights creatively bend and damage constitutional rights, whether it is for access to oil, copper, uranium, or other natural resources. In this instance, religious freedom was attacked; however, when this inevitably happens again, it is unclear as to which essential right will be perverted next.

Categories: Domestic Affairs