As I was sorting my old digital files, I came across a project from high school that I did in my junior year. We were tasked with creating a video tribute memorializing the lives of Vietnam veterans who had died and whose names were listed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in D.C.

I was randomly assigned the name Christopher Braybrooke. Over days of research, I managed to find only the slightest bit of information about him even after scouring the Internet. He was from New Jersey, had been a Lieutenant Colonel in the Air Force, and had died on October 8th, 1967 in Thua Thien Province, Vietnam. Not much in the way of creating a meaningful memorial.

Despite the uncertainties of cold emailing, I got in contact with Valerie and Scott Braybrooke, Christopher’s wife and son. Over phone and email, Valerie and Scott graciously shared the life of their loved one with a complete stranger. Their stories and photographs painted a deep and colorful portrait of a man who lived for others, and whose loss deeply impacted those he lived for.

The project memorializing Christopher Braybrooke was, and still is, the most meaningful project I have ever had the privilege of completing. The heroism of Christopher’s story and character has become increasingly impactful to me in an age when people struggle to connect with each other on a deeper level, when Americans don’t trust each other or our institutions, and when the social media landscape incentivizes people to say and do awful things to gain followers and influence.

Now, four years after the video tribute, I want to make a tribute in writing. This long form medium will do far greater justice to Christopher’s story, and will emphasize its importance.

This is the story of a man who died in the service of his country, and a woman who was left to pick up the pieces of a family left behind.

_________

Early Years

Christopher “Kit” Braybrooke was born in Hackettstown, New Jersey on March 25th, 1928. The nickname “Kit” came from St. Kitts Island, officially named Saint Christopher. He was raised in a log cabin in Boonton, New Jersey — a rural, idyllic American small town, surrounded by wilderness and rivers made for fishing.

Christopher’s parents were immigrants from England. His father, Walter Leonard Braybrooke, was a well known civil engineer who had served with the British army in Africa during World War I, and at age 49 had volunteered to serve in the U.S Army as an officer during World War II. Christopher’s mother, Netta Rose Foyle Braybrooke, was described as an adoring, loving wife who only worked inside and never got a driver’s license.

Christopher had two siblings, David and Timothy. David was the eldest and served in the army during World War II. After the war, he resumed his education and received a B.A. from Harvard, an M.A. and Ph.D. from Cornell, and an LL.D. from Dalhousie. He taught philosophy and government at Dalhousie, and later in his life, taught government at UT Austin. David died in 2013.

Timothy Braybrooke, on the other hand, died when he was six years old of a disease that was treatable. His loss profoundly affected the Braybrooke family, and he was always in their thoughts.

During his adolescence, Christopher had already begun to display a desire to serve others and pursue excellence. He attended Boonton High School, and when the school band needed a pianist, he learned to play the instrument. Christopher was also class president, a Boy Scout, Editor in Chief of the Wampus school paper, President of the National Honor Society and a National Merit Scholarship finalist.

In addition, Christopher was a devout Episcopalian. His early service to the church would foster a dedication to faith and community that would last his entire life.

“When the priest asked for one of the several boys who served as acolytes to take the 8:00 a.m. service, only Kit volunteered. I expect his volunteerism had as much to do with his appreciation of the dawn, so unusual in most teenagers, as with his dedication to the church.” -Valerie Braybrooke

Joining the military

As he finished up high school, Christopher applied to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York and received a four-year scholarship. Despite this life-changing opportunity, he chose to enlist in the military, as he felt this was the best way he could contribute to his country.

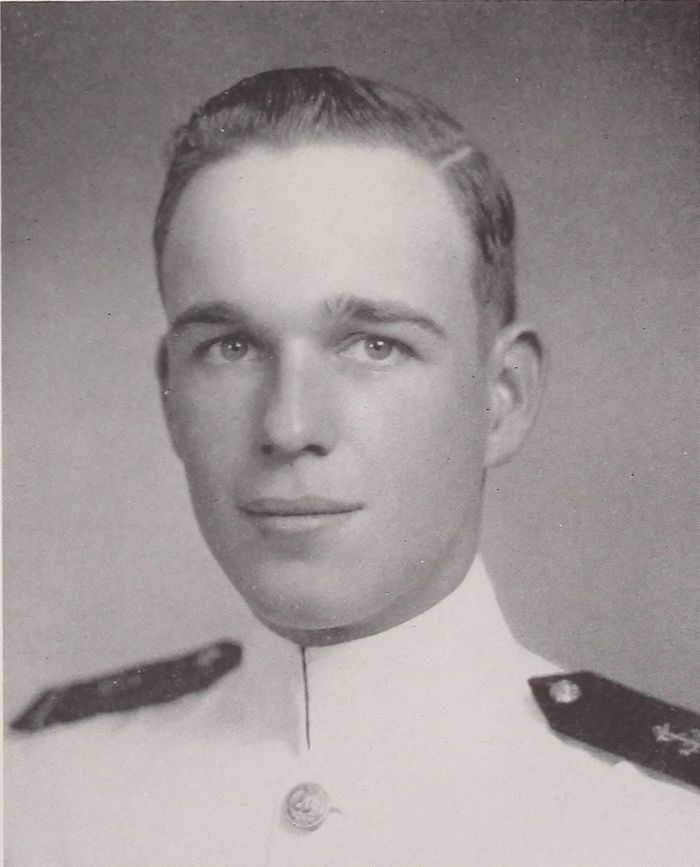

From 1946 to 1950, Christopher attended the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland after competing for and receiving a recommendation. According to the 1950 edition of the Lucky Bag, the United States Naval Academy yearbook for graduating classes:

“Kit devoted much of his time to athletics; he often came in battered and bruised from Batt Lacrosse, but still wearing his perennially nonchalant smile. Attractive women were his weakness, but a good argument excited him too. He won many of both. Sunnybrooke’s success at the Academy can be traced to his thoroughness of preparation, his reliability, and his friendly and sincere personality.”

In spite of Christopher’s success at the Naval Academy, he chose to part ways and join the Air Force. The decision came down, in part, to seasickness.

“At Annapolis all midshipmen spent summers serving on ships at sea. Standing on the bow of a destroyer that was pitching and yawing in rough waters, Kit decided that the Navy wasn’t right for him and he changed his goal to flying planes in the Air Force. The AF, with no academy of its own yet, plucked grads from both academies.” -Valerie Braybrooke

In the Air Force, Christopher completed pilot training in August 1951, and advanced pilot training at Ellington Air Base, Texas. One incident from the time in particular illustrates his attention to detail.

“In his first ER (effectiveness report), [Christopher’s] commander faulted him for having dirty shoes. My husband was the neatest person I, or his parents, have ever known — he polished shoes daily; white-washed his sneakers before playing tennis; never dropped clothing around the house; always shaved daily when other men ‘let their faces rest’ on weekends; and I never saw him with a hair out of place, no matter what he was doing. The laughable accusation was appealed and won.” -Valerie Braybrooke

Christopher’s military service would span 16 years, beginning with an assignment to the 34th Troop Carrier Squadron in 1953 — an outfit known as the “Kyushu Gypsies.” Christopher’s role was to fly personnel and cargo out of Japan to bases all over Korea.

“The Japanese government even got [Christopher] to do some crop dusting for them which, from the photo of them afterward, had also taught the crew the effects of grateful saki. While in Japan he took a photograph of every flowering cherry tree on the islands. Thousands!” -Valerie Braybrooke

Love, Marriage, and Work

In 1955, Christopher finished his service with the Kyushu Gypsies. For the next two years, he attended MIT, where he received a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering in June of 1957.

It was during this time that Christopher fell in love. He lived in a Cambridge apartment that was shared with two other men; next door lived Valerie Frank and two other women. Out of the three men and three girls, two couples emerged, one of which was Christopher Braybrooke and Valerie Frank.

Valerie was from Bridgeport, Connecticut. She was a graduate of Rosemary Hall and attended Smith College, studying for an art history degree, when she met Christopher. They were engaged and married in 1957.

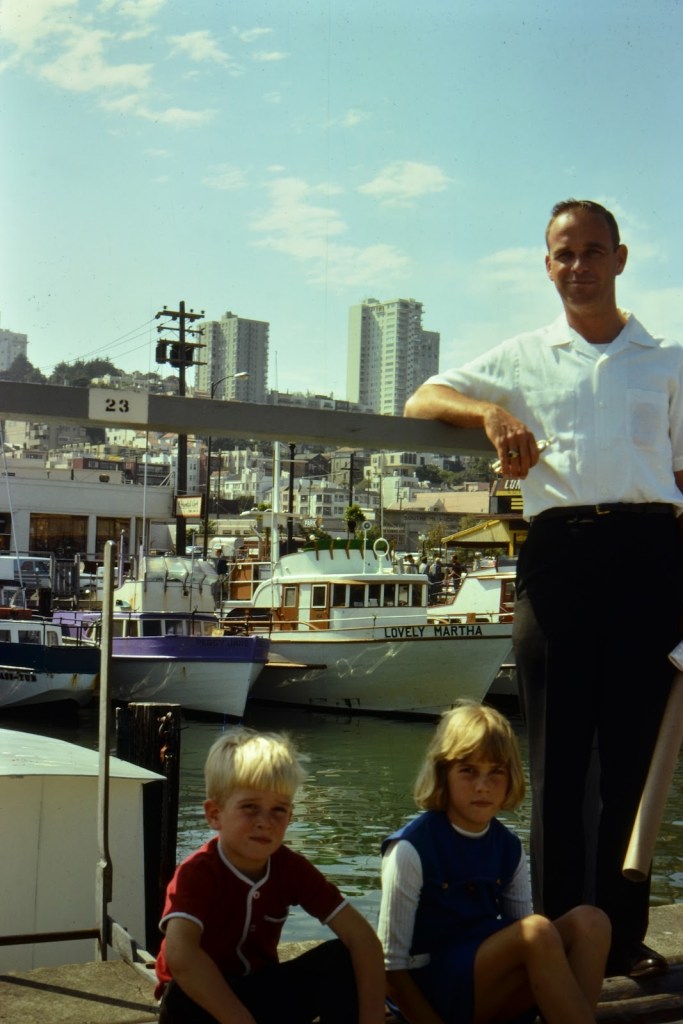

For the next six years, Christopher was stationed at Eglin Air Force Base in the panhandle of Florida. In 1958, Christopher and Valerie had a daughter, Kristen. In 1961, they welcomed a son, Scott.

It was here that Christopher served as a Project Officer on the GAM-83 air to ground missile, in addition to other projects. Christopher and Valerie rented a house in Florida without air conditioning, a decision Valerie especially detested, as she was a New England person through and through.

It was also during this time that Valerie was forced to compete with the other love of her husband’s life.

“During those years at Eglin we took numerous TDYs (temporary duty). The one to Denver was like a second honeymoon with afternoons free to roam the mountains and have meals out of the apartment. One evening I was looking forward to having dinner at a fancy restaurant but on the way Kit stopped at the end of the airport runway to show me his favorite C-130 making takeoffs and landings. He was enthralled with its engine sound and for the longest time he oohed and aahed while my stomach growled with hunger. He would have taken the plane home if he could.” -Valerie Braybrooke

During his time in Florida, Christopher worked with civilian contractors to prepare the sharing of new missile systems with officers representing Canada and England.

“Low military pay and deep pockets of civilian contractors presented temptations for bribery and influence. Despite strict orders, some officers simply were not able to resist, but my husband earned the respectful ‘Mr. Honesty’ compliment among his colleagues. No surprise to me.” -Valerie Braybrooke

After this project, Christopher attended Air Command and Staff college at Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, and was elected to the Order of the Daedalians, a fraternal organization for Air Force officers. He was then assigned to the Pentagon in Research and Development from 1964 to 1967, where he worked on the notable F-111 and C-5 programs.

Even here, Christopher’s steadfast dedication to service, whether it was to his country or community, shone through.

“Christopher was assigned to R&D at the Pentagon, on the Virginia side of the Potomac. We moved to the western most housing in Northern Virginia where we took on the habits of being civilians by being active in the neighborhood: Kit, popular as ever, was elected president of the Civic Association.

Forest and fields stretched west of us except for the tiny Episcopal Church that we joined and were soon tasked with building a much larger church in anticipation of the westward-growing population: Kit was elected to the Vestry and made responsible for planning much of the new building.” -Valerie Braybrooke

Death and Loss

When Christopher began his service in Vietnam on September 22, 1967, the war had been ongoing for two and a half years.

By this point, he had made the switch from flying fighters to flying tactical planes. Christopher had spent the summer flying the C-130 at Sewart Air Force Base, Tennessee, before being assigned to the 773rd Tactical Airlift Squadron. Christopher’s role was non-combat related; he was to fly personnel and supplies throughout Vietnam, including Red Cross missions.

During this time, the remaining members of the Braybrooke family — Valerie, the two kids, and a dog — lived in the Philippines.

On October 8th, 1967, in Thua Thien Province, Christopher was flying as a copilot on C-130B, serial 61-2649. The plane crashed into a cloud covered mountain in poor weather; the wreckage was found two days later 150 feet below the summit of the 1,850 foot mountain.

Valerie was shaken to the core by the news of Christopher’s sudden death.

“Two weeks after arriving, on Kit’s first sortie with his section of the squadron flying personnel and supplies throughout Vietnam, I was informed that his plane was missing. No facts. Several days later the plane was found and I was informed that ‘he could not have lived.’ No one aboard had lived.

I asked questions of everyone and received no answers – only the assurance that my husband had died instantaneously. No one would give me facts or information: I was supposed to be satisfied with having no facts when there was no body, nor body parts retrieved and not even the finding of dog tags. Nothing for proof.”-Valerie Braybrooke

Left with more questions than answers, Valerie would continue asking about the nature of the Vietnam War and the details surrounding her husband’s death. She found herself becoming increasingly frustrated by a lack of transparency from military leadership, but eventually found the answers she was looking for.

“While awaiting our diminished family’s return to the U.S., the pilots in the other part of the squadron arranged to ‘baby-sit’ me on a daily rotating schedule. None of them knew me, nor I them. The first one to come probably expected to have to pull the hysterical widow off the walls. He got a surprise. An unwritten rule in the air force is that husbands do not reveal maneuvers to wives, nor should they discuss politics, and definitely never disparage the Commander in Chief.

On his first visit, I asked Baby-sitter #1 to explain the Vietnam War. The situation was awkward in the extreme. He was stunned and unable to articulate what he had probably never expressed out loud before, much less to a stranger. Baby-sitter #2 had apparently been forewarned and was able to tell me more. After half a dozen difficult baby-sitting grilling encounters with these wonderful people, I realized that they were — maybe for the first time — encountering questions with answers that forced them to see two things clearly: (1) They were telling me that my husband’s death was utterly useless and (2) They themselves were questioning their career that wasted its pilots.

Vietnam, they each revealed slowly, was an unwinnable, bloody situation being micromanaged by a career politician in the White House; the Joint Chiefs of Staff were no help to the military commanders on the ground; and Congress was too lazy to control money or legislation. The undeclared war was a useless endeavor for everyone. That was in 1967. Many of these same pilots, I learned later, resigned from the air force way before they had ever originally intended.

At home I continued to ask questions and write letters trying to discover the reason for Kit’s death. I was constantly put off and passed off to yet another possible source. To no avail. Finally, five years later, I met a Naval aviator at a party who recognized my name and proceeded to recap the circumstances of my husband’s death. It seems the U.S. ground controller at Hanoi had read the wrong scope for the plane’s takeoff and vectored it into a mountain. The accident must have been a case study for all pilots and aviators alike, but direct questions by the person most involved were ignored.” -Valerie Braybrooke

Remembrance

In the end, Christopher Braybrooke was killed not by enemy fire, but by a costly error by American ground control. He was only 39 years old.

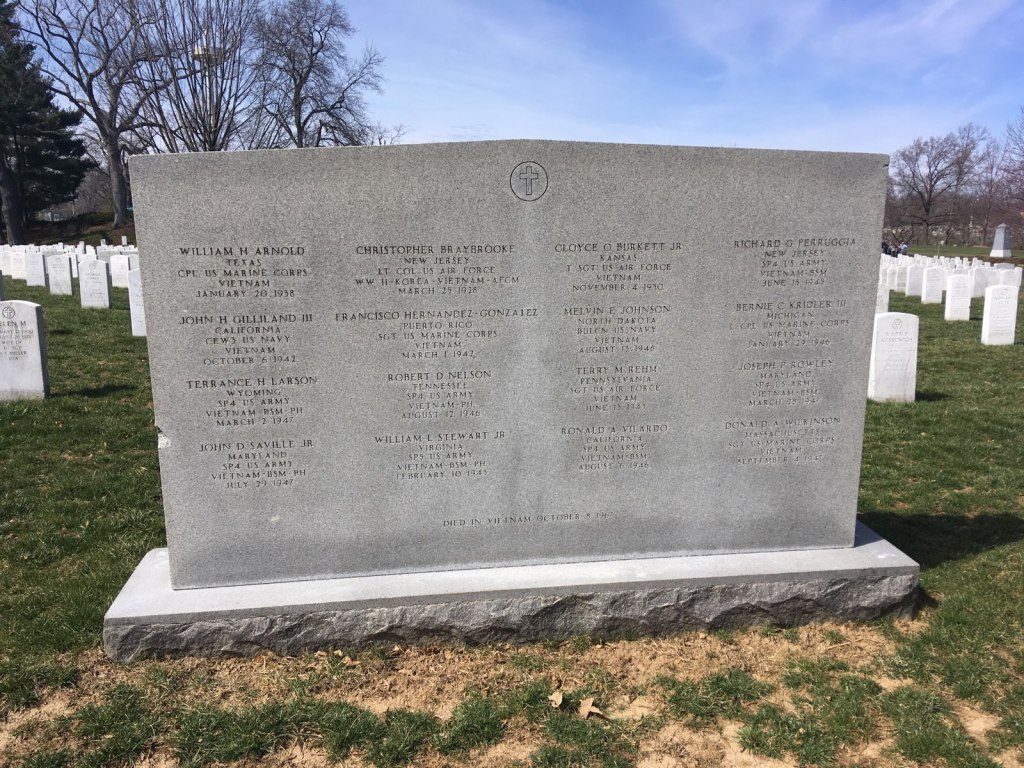

Major Robert W. Anderson (the pilot) and navigator Scott M. Burkett died alongside him in the same crash. Because it wasn’t possible to make individual identifications, a group burial was made at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

On panel 27E, 73 of the Vietnam War Memorial, Christopher’s name can be found. His alma mater, Boonton High School in New Jersey, dedicated a portion of their library to Christopher, where a wooden carving of him now stands.

Christopher held the Air Force commendation medal, the National Defense Service Medal with one bronze star, the Korean service medal, the Vietnam service medal with one bronze star, and the Air Force longevity service award ribbon with three bone oak leaf clusters.

At the time of his death, Christopher was survived by his wife Valerie, his children Scott and Kristen, his parents, and his brother David. Today, Valerie, Scott and Kristen are still alive.

Valerie never remarried.

“Christopher, like his father before him, was one of the finest people I have known. Military service was the closest Kit could get to doing the most and giving his best for our government. We received three U.S. flags — One at a memorial service in the Philippines; one at the memorial service at our Episcopal Church at home, and one from the military ceremony at Arlington Cemetery for those named on the cenotaph. One of those folded flags I placed inside the casket of my father-in-law, dressed in his WWII US Army uniform, who died at age 97.” -Valerie Braybrooke

Three Lessons for Us, the Living

1. The effects of war cannot be understated.

Today, we live in an era where Americans of both parties feel comfortable using violence to achieve their political ends. Some yearn for a civil war — a chance to enact punishment on the other side of the political aisle. While war can be a necessary tool to preserve peace and our most cherished ideals, it should not be taken so lightly.

The death of even a single individual can cause wide ripples in history that transcend generations and scar those far removed from the fighting. The remembrances of Christopher’s daughter, Kristen, and his granddaughter are a testament to this truth.

“Hi Dad, Long time no see.

My daughters are grown up now, but you have two new, tiny grandsons Nicholas and Kit. Scott named the sweet one after you! He says he’s as gentle and polite as you were, raising his tiny hand when he wants attention. Nicholas is the rowdy one who yells a lot. I wish you could see them and hold them. You would’ve been such a happy Grandad.

I’m glad I was just old enough to know you as a happy Daddy. I wish it had been longer than 8 1/2 years. I was just getting good at the ‘wrapping-Daddy-around-my-little-finger’ when you were killed. I set the dinner table for you for over a year, and Scott waited every night out on the steps for you to come home.

Mom must have suffered so much from losing the best man she’d ever known and loved, but she never showed it. She never, ever, got over losing you. I don’t think any of us has. Not a day goes by that I don’t think of you. And miss you. And whenever I hear ‘Taps’, I just cry and cry for the Daddy I knew and the Daddy I needed, but is dead.

I loved you then, I love you still, Daddy’s girl”

– Kristen Braybrooke, November 22, 1999

_________

“My grandfather died when my mom was eight years old. I never got to meet him, but his loss has affected our family ever since. I hope today is the last day anyone’s loved one will be lost to war.”

– 3/28/13

2. Follow real heroes.

The Japanese author Mishima said it’s impossible for modern man to die a hero’s death. There is a great deal of truth in this statement, as most of us will die ordinary deaths. But while one may not die the death of a hero, living the life of one is still possible.

To do so, we can follow the example of the Braybrookes in the ways that they lived life as rightly as possible in spite of tragedy, and in the ways that they took care of others — be it their family or community.

Christopher was a hero — he exemplified the virtues of service and sacrifice as a veteran, Christian, and family man. From his early volunteer work in the church to his service in Vietnam, Christopher showed a commitment to the greater good and pursued excellence in all he could. Even considering the national trauma of the Vietnam War, there is something to be said for taking on duties so that others, who otherwise would have had to take them, didn’t have to.

However, Christopher is not the only hero of his own story. Valerie Braybrooke is a heroine in her own right, exemplifying the virtues of service in sacrifice in a different, but every bit as powerful, way. After her husband’s death, she was a single mother to two children, with only a bachelor’s degree in art history. She went back to school to pursue her master’s degree before eventually finding work in a museum. One can only imagine the immense turmoil Valerie endured after losing the love of her life. She displayed great strength and courage not only in scrambling to take care of the family on her own, but also in pushing to find answers for Christopher’s death.

3. The past matters.

My mom told me once that “we walk on the dead.”

She was right — there’s something hauntingly beautiful about those who have come before and how we walk on their remains no matter which path we end up choosing.

Looking back on Christopher’s story, it’s strange to feel a tentative connection to someone who lived in a different era and came from a different background. There’s a unique familiarity and intimacy that you get from looking at their photos and story, and soon you begin to feel like you’ve found a long lost friend or father.

At times, I’ve found myself thinking about Christopher Braybrooke or seeing his face pop up in my mind when I face something difficult, or when I need a reminder to stick to a moral principle.

I am not at all a religious person, but the drive to seek heroes out for guidance lies within everyone. History and narrative really can guide the way we live in the present by touching the deepest parts of what moves us as human beings.

As Chekhov writes in “The Student,” a short story in which the main character Ivan recounts the Story of Peter and makes his listeners cry:

“‘The past,’ [Ivan] thought, ‘is linked with the present by an unbroken chain of events flowing one out of another.’ And it seemed to him that he had just seen both ends of that chain; that when he touched one end the other quivered.”

The Story of Christopher Braybrooke moves the present because it guides us on the core questions that make us human beings.

How can we be heroic? How do we live rightly in spite of the bad? And how do we love and care for one another?

In the end, there are many ways to be a hero — to live rightly, to care for others. But the underlying values of heroism rhyme from person to person and across time. Service and sacrifice, both of which entail the other, are these enduring values.

They don’t look the same for everyone, but therein lies the beauty of living a heroic life.

Categories: Culture, Domestic Affairs, Interviews, Philosophy

Thank you for this moving article. My Dad, Alex Richardson, was Kit’s best friend in high school. I have a color photo of the two of them together at the Seoul Airbase in Korea, obviously taken at the same time as one of the pictures in your article. Dad was a Lieutenant in the Army Signal Corps at the time, stationed in Korea.

LikeLike

Thank you for taking the time to read the article and leave a comment! It means a lot 🙂

LikeLike

A lovely project. Christopher is my grandfather, via my mom, Kristen. And I wrote the comment published below hers (it was originally posted on a military site where strangers were posting war-glory comments below Christopher’s bio, seemingly ignoring the radiating, persistent toll war has on families around the world). It is ethically wrong, in my opinion, to express gratitude for service, without expressing a goal to end war. I appreciate, Mr. Shettigar, your thought-provoking perspective which makes room for both appreciation of the service and acknowledgement of the damage it brought.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your comment! It was amazing to learn about your grandfather and grandmother, who are continued inspirations for me. I tried my best to balance discussing the virtue of serving one’s country while also recognizing how damaging war is, so I’m glad that came through in the writing. Wishing you and your family the best – Naran

LikeLike