“Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” – Robert Oppenheimer quoting the Bhagavad Gita

“There were people crying out for help, calling after members of their family. I saw a schoolgirl with her eye hanging out of its socket. People looked like ghosts, bleeding and trying to walk before collapsing. Some had lost limbs. There were charred bodies everywhere, including in the river. I looked down and saw a man clutching a hole in his stomach, trying to stop his organs from spilling out. The smell of burning flesh was overpowering.” – Sunao Tsuboi, Hiroshima survivor

“We received the news with quiet disbelief coupled with an indescribable sense of relief. We thought the Japanese would never surrender. Many refused to believe it. Sitting in silence, we remembered our dead. So many dead. So many maimed. So many bright futures consigned to the ashes of the past. So many dreams lost in the madness that had engulfed us. Except for a few widely scattered shouts of joy, the survivors of the abyss sat hollow-eyed and silent, trying to comprehend a world without war.” – Eugene Sledge, US Marine

____________________________________________

In the wake of Nolan’s Oppenheimer, there has been a renewed interest in whether the use of the atomic bombs against Japan in 1945 was justified.

Critics of the bombings assert that they were not necessary to ensure a Japanese surrender; that they were motivated by a combination of anti-Japanese racism and a desire to show off military strength. On the other hand, supporters of the bombings argue that the attacks were necessary to secure a surrender and that they ultimately saved both Japanese and American lives in the long run.

In this long form article, I will go line by line, question by question, to achieve as objective an answer as possible regarding whether use of the bombs was morally right. Overall, I believe that the atomic bombings were human tragedies that were nonetheless morally justified — although there is a gray area regarding the Soviet Union that is worth mentioning.

In coming to this conclusion, I focus specifically on President Harry Truman’s reasoning, as it was he who ultimately made the decision to drop the bombs.

What did Truman know?

- High Casualties in the Pacific

The first thing Truman knew at the time of dropping the bombs was the unyielding brutality of the Pacific War.

The Japanese military, while ill equipped, hindered by political infighting between the army and navy, and infatuated by suicidal and largely ineffective banzai charges, was fanatically tenacious.

Smarter Japanese generals, such as Kuribayashi on Iwo Jima, refrained from wasting his men via banzai charges and instead turned the island into a death trap of tunnels and guerilla fighting that led to horrendous casualties on US marines. The Japanese soldier did not surrender due to both a belief in the dishonor of such an action and the propaganda that Americans would torture them. Even after the end of World War II, there are numerous accounts of Japanese “holdouts” — soldiers who continued fighting sometimes up to 30 years after Japan’s defeat.

The Japanese soldier was also brutal.

Such savagery was instilled in soldiers starting at the first moment of training; Japanese officers would often beat recruits until they nearly died and had them do bayonet training on live prisoners. There are numerous reports of the Japanese feigning surrender only to blow up Allied soldiers with hidden grenades. In almost every occupied territory throughout Asia — from China to Korea to the Philippines — the Japanese perpetrated mass rape, executions, and torture. In Unit 731, in northern China, the Japanese performed live vivisections, biological testing, and forced pregnancies on prisoners.

This is not to say that Japanese soldiers were not human beings. Kamikaze pilots, for instance, were not all robotically programmed fanatics but were sometimes relatively liberal university students who had been exposed to Western ideas through literature and philosophy and were tragically forced to die.

Nonetheless, it is undeniable that the Imperial Japanese military was, in many ways, a modern day Sparta — a nation that indoctrinated its youth in war and brainwashed their soldiers with unending cruelty as a means to serve the state.

In response to the Japanese soldiers’ brutality and fanaticism, and undeniably accentuated by the racial attitudes of the time, American soldiers fought tooth and nail on Pacific islands. They refrained from taking prisoners and took Japanese body parts as trophies.

American strategic bombing, revamped by Curtis LeMay, also took a more aggressive approach to attacking Japanese industry. Japanese homes and wartime manufacturing were often intermingled; instead of trying to separate between the two — which was probably technologically impossible at the time — American B-29 bombers firebombed all of it. The infamous March 1945 firebombing of Tokyo killed roughly 100,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and is considered one of the deadliest air raids of all time.

Despite this, the Japanese still did not surrender. A month later in April of 1945 began the Battle of Okinawa. Around 12,000 Americans, including General Buckner, were killed, while 100,000 Japanese soldiers perished. Between 40,000 to 150,000 Okinawan civilians died in the bloodiest battle of the Pacific War.

The casualty numbers from Okinawa were in Truman’s mind as he debated what to do with Japan. Each day that the conflict continued meant not only more American and Japanese lives lost, but also more Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Malaysian lives. Japan still possessed occupied territory even as they were losing their holdings in the Pacific. Prolonging the war meant the continuation of Japanese atrocities against their Asian neighbors.

- Japan’s lack of willingness to surrender

Truman, as revealed in his diaries prior to the atomic bombings, believed that the Japanese would not surrender short of using nuclear weapons.

This belief was supported by the Japanese rejection of unconditional surrender as outlined in the Potsdam Declaration of July 26th, 1945, even as mainland Japan was being ravaged by firebombs and their holdings in the Pacific dwindled. Truman’s belief was also supported by the aforementioned Battle of Okinawa, which saw massive casualties for both sides and perfectly displayed the “never surrender” ethos of Japanese soldiers.

Some argue that the Japanese were actually willing to surrender prior to Hiroshima. There is a grain of truth to this: within the Japanese cabinet there was a minority element that wanted to end the war by using the Soviet Union as a mediator to bargain for a conditional surrender. However, the peace cabinet’s overtures to the Soviets were minor and harshly opposed by the more dominant militaristic faction of the Japanese cabinet. The Japanese overtures were ultimately futile and meaningless attempts by a small faction that did not constitute a legitimate movement within Japanese decision making to surrender.

Similar allegations are made with regards to other “peace feelers” that exaggerate the significance of these incidents. The reality is that Japan never made official peace offers or even stipulated terms because such actions would have been shot down by the militaristic camp. The Americans (and probably Truman) were aware of these overtures because they had deciphered Japanese codes, but interpreted them as suggesting that the Japanese cabinet was unwilling to surrender.

Rather, it was clear that a dominant portion of the Japanese cabinet was committed to fighting a war until the bitter end, even if it meant sacrificing the Japanese people as reflected in the late war propaganda movement termed “the glorious death of 100 million.”

One point of uncertainty that could be raised is whether the Allies could have gotten Japan to surrender sooner if they had offered to preserve the Emperor.

Given testimony by some Americans at the time, it is possible that Japan may have surrendered sooner if this stipulation had been promised. However, Japan did not make an official peace offer with these exact terms until after the Nagasaki bombing — a fact which casts doubt on the claim that they would have surrendered earlier if given the option.

In hindsight, even if Japan would have surrendered earlier, it is understandable why Truman may not have wanted to include protection of the Emperor as a bargaining chip.

Japan was a fearsome enemy that needed a massive social restructuring to ensure a true end to the war. The Japanese islands had never been conquered in history — even the Mongols had failed. The Japanese also viewed themselves as racially and culturally superior to other Asians and Westerners. Determining the proper role of the Emperor would require total American control over Japan — this could only be achieved by unconditional surrender. Giving the Japanese a conditional surrender beforehand could influence them to bargain for more out of a negotiated surrender — thus prolonging the bloody war.

- Options to end the war

On July 16th, Truman was aware that the atomic bomb was functional and could be used against Japan.

Initially, Truman and his advisors also discussed alternative options to earn Japan’s surrender. These included the aforementioned alteration on unconditional surrender, the invasion of mainland Japan, the naval blockade and continued strategic bombing campaign, and a demonstration of the bomb.

The hypothesized Invasion of Japan is a controversial area as many today discuss the true projected casualties of such an endeavor. However, it is undeniable that Truman believed such an invasion would be immensely costly, even if he gave (or was given) differing or inaccurate casualty projections. Simply based on the recent Battle of Okinawa, Truman could see a mainland invasion that would kill scores of American soldiers.

The naval blockade and strategic bombing option was also floated around, particularly by members of the Navy. Truman likely didn’t want to go through with this option because he felt it would prolong the war. In hindsight, blockading was probably more inhumane than the use of the atomic bombs. As horrible as the bombs were — one can read about the children killed, the vaporized “shadow” of a man — a naval blockade would have meant starving Japan of medical supplies and food. Many civilians would have died slowly of starvation and malnutrition, while more Japanese cities burned from strategic bombing.

On the subject of demonstrating the nuclear bomb, Truman was also skeptical. If a demonstration failed, then it could send encouraging signs to the Japanese to continue their war effort against the U.S.

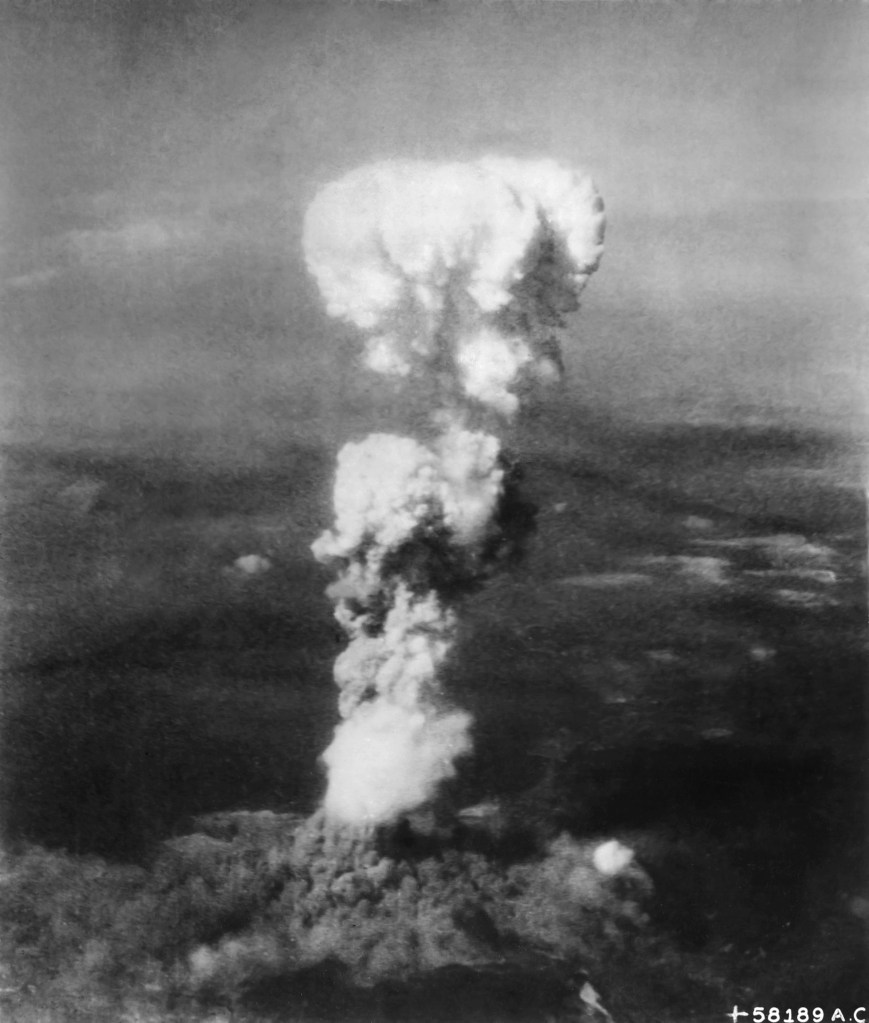

Truman was also not alone in formulating his decision. He was aided by an Interim Committee that he formed specifically to advise him on the use of the atomic bomb. This committee was composed of “respected statesmen and scientists close to the war effort” and unanimously recommended the full use of the bomb against Japan over the summer of 1945, prior to the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6th and Nagasaki on August 9th.

Only one man from the Interim Committee changed his mind; Assistant Secretary Ralph Bard wrote a memo in July to Secretary of War Stimson in which he urged the United States to give Japan advance warning and assurances that the Emperor would be maintained post war.

In addition, most of the scientists involved with the Manhattan Project believed the bomb should be used in some capacity, although there were some minor cases of dissent — such as Szilard’s petition to Truman.

In terms of military opposition, there were famous cases of high ranking officials, from Eisenhower to MacArthur, decrying the use of the bomb after the war. However, it is hard to find direct evidence from before the bombings that these men dissented against Truman’s thinking in a meaningful way.

- The Soviets would fight Japan

The United States’ position to Soviet entrance into the Pacific War was generally positive for most of World War II. At the Yalta Conference in February of 1945, FDR and the Allies made concessions to Stalin to convince him to renege on the USSR’s pact with Japan and enter the conflict.

Truman was aware that Stalin planned to enter the War against Japan in mid-August of 1945. According to a letter Truman wrote to his wife on July 18th of 1945 (two days after the Los Alamos testing results), he appeared genuinely excited that the Soviets would join the theater and end the war quickly, thus saving young American lives.

At the same time, Truman also seemed wary (quite justifiably) of Stalin later that month; in his personal diary on July 25th, he notes that it was good that neither Hitler or Stalin obtained the nuclear bomb. It remains an open question as to whether, and how much, Truman’s attitude towards Soviet involvement shifted as July wore on into August.

What motivated Truman?

Did Truman want to scare the Soviets?

Whether Truman dropped the atomic bombs in part to deter Soviet influence in post war Japan is a gray area.

The claim that Truman was solely determined to drop the bombs based on this is implausible; as demonstrated in the first section of this piece, Truman was motivated hugely by a desire to end the Pacific War.

However, I wasn’t able to fully disprove or prove that there wasn’t at least some motivation to deter the Soviets.

While Truman was certainly in favor of Soviet entry in early to mid-July, it is uncertain whether he changed his mind as he became more certain that the nuclear bomb could be used. There was indeed a shift in necessity for Soviet intervention in the war; once Americans had the atomic bomb, the US had a strategic advantage and did not need the Soviets to put pressure on an intransigent Japanese leadership. In addition, Secretary of State Byrnes, one of Truman’s advisors, was very much against the USSR, and was allegedly in favor of using the bomb at least in part to prevent Soviet influence after the war.

Despite this, I couldn’t find direct evidence that Truman shifted his stance against Soviet involvement after the Los Alamos tests or dropped the bombs due to Byrnes’s reasoning.

Rather, it seems that the chief motivator for Truman, given what he knew at the time and what his personal diaries reflect, was to end the Pacific War. There is, however, a chance that a secondary motive — dropping the bombs to deter Soviet influence in Japan — existed as well.

Was Truman motivated by racism?

At first glance, it seems possible that racial sentiments colored Truman’s thinking at the time.

In the aftermath of Nagasaki and the subsequent pleas from a Protestant clergyman to stop future atomic bombings, Truman said: “The only language [the Japanese] seem to understand is the one we have been using to bombard them. When you have to deal with a beast you have to treat him as a beast.”

And yet, after Hiroshima, Truman resisted a call from Senator Richard B. Russell to drop as many atomic bombs as possible, stating:

“I know that Japan is a terribly cruel and uncivilized nation in warfare but I can’t bring myself to believe that because they are beasts, we should ourselves act in that same manner. For myself I certainly regret the necessity of wiping out whole populations because of the ‘pigheadedness’ of the leaders of a nation, and, for your information, I am not going to do it unless absolutely necessary.”

Of course, Truman still refers to Japanese people as beasts.

In part, this is due to the racism of the time. Americans held a far more negative racial view of Japanese people than they did Germans for two primary reasons: the physical and cultural differences between Japanese and Americans was far wider, and the injustice of Japanese military actions — from the surprise attack at Pearl Harbor to war crimes such as the Bataan Death March — inspired tremendous racial hatred. Propaganda from the time, including some done by Dr. Seuss, depicted the Japanese as rats and monsters. Indeed, the American government under FDR placed 120,000 Japanese American citizens in internment camps without any due process.

Despite this, it seems that Truman was more so motivated by a desire to end the war than he was by racial animus.

The Japanese military was incredibly brutal and unwavering — his comments about the Japanese as beasts, while dehumanizing, likely reflect the frustration felt by a president who was fighting a costly war against an enemy that didn’t know how to quit. Truman admitted that he felt a “human feeling for the women and children of Japan,” even as his primary objective was to save American lives. He was also reportedly ashamed of Japanese internment, and even presented a citation to a U.S. Army Japanese American regiment in which he stated: “You fought not only the enemy, but you fought prejudice — and you have won.”

The Problem of Hindsight

Before pulling everything together and coming to a conclusion, I wish to briefly address the problem of using hindsight in evaluating the morality of the bombings.

Critics of the bombings often mention that page 107 of the 1946 United States Air Force Survey – a report to determine the efficacy of Allied bombing against the Axis powers – concluded that the atomic bombs were not necessary to earn Japan’s surrender.

However, this survey is not relevant to the question at hand because it is based on information gathered after the war. What matters in determining the morality of the atomic bombings is the information and motivations that Truman had at the time of his decision. To go back in time and judge the decision based on information that was gathered after the fact sets up a superhuman standard by which to judge morality.

The hindsight argument also applies to the arguably strong assertions that the Soviet Invasion of Manchuria on August 8th was more influential in compelling Japanese surrender than the atomic bombs were. While we will never know for sure, the matter is simply not important in determining whether the bombs were moral since the claim depends on information that Truman could not have known at the time.

Conclusion

In short, Truman knew that all sides were paying a high price in the Pacific War, the Japanese were unwilling to surrender, there were no other viable options to end the war, and that the Soviets would enter the Pacific War. He was primarily motivated to drop the bombs so that he could end the Pacific War — but there is also a possibility that he was motivated in part to deter Soviet influence in the region.

There are therefore three possible intentions behind Truman’s decision to drop the bombs — two of which are morally good. In determining the “morality” of each option, I consider whether Truman’s intention was both reasonable and good. I take it as a given for all the possibilities that his intention in ending the Pacific War was reasonable and good, as supported by the arguments made in my article. The differentiating factor is whether the potential motive of deterring the Soviets was morally good, meaning that the motivation was both virtuous and reasonably aimed to minimize harm.

The first possibility is that Truman dropped the bombs solely to end the Pacific War — a morally good decision given what Truman knew and was motivated by at the time.

The second possibility is that Truman dropped the bombs partly to deter the Soviets for the sake of Japanese lives and American power. This would be a morally good decision as well, since Soviet rule over Japan would have had brutal consequences, as it did in Korea and Vietnam. Truman, as discussed earlier, was at the very least skeptical of Stalin as a leader in late July of 1945. It is not unthinkable that Truman would be afraid, for moral reasons, of letting Stalin conquer more territory. While this interpretation involves reading Truman’s mind, and is therefore hard to back up with direct evidence, the same applies for any type of claim that he dropped the bombs to deter Soviet influence.

The third possibility is that Truman dropped the bombs partly to deter the Soviets for the sake of American power itself. This action would be morally ambiguous; while one motivation, ending the Pacific War, is good, the other is at the very least morally bankrupt. Seeking to increase power just for power’s sake — without regard to the human lives that American rule, as opposed to Soviet rule, would save — is not a virtuous motivation to have. Therefore, I consider this option to be morally gray given the conflicting moralities of the motivations at play.

Overall, I believe it was most likely that the atomic bombings were morally justified, meaning that possibilities one and two are far more likely than possibility three.

As stated previously, I could not find any direct evidence proving or disproving that Truman was not at least partially interested in deterring the Soviets. In addition, most of the primary documents I found explicitly state that Truman’s motivation was to end the Pacific War. Furthermore, while Truman’s chief concern was to save American lives — and he seemed callous and even dehumanizing at times to the Japanese — he was also partly concerned for the wellbeing of Japanese innocents. Taking all this into account, it seems most plausible that if there was a secondary motivation to deter Soviet influence in post war Japan, that it was motivated out of humanity rather than a Machiavellian desire for power itself.

In the end, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were human tragedies regardless of the motivations for and necessity of dropping the bombs. Nonetheless, the atomic bombings deserve to be remembered both as a testament to the horror of nuclear war but also the stubbornness and brutality of Japanese military leadership at the time.

Categories: Foreign Affairs

Great read!

LikeLike