Note: This article is part one of a series.

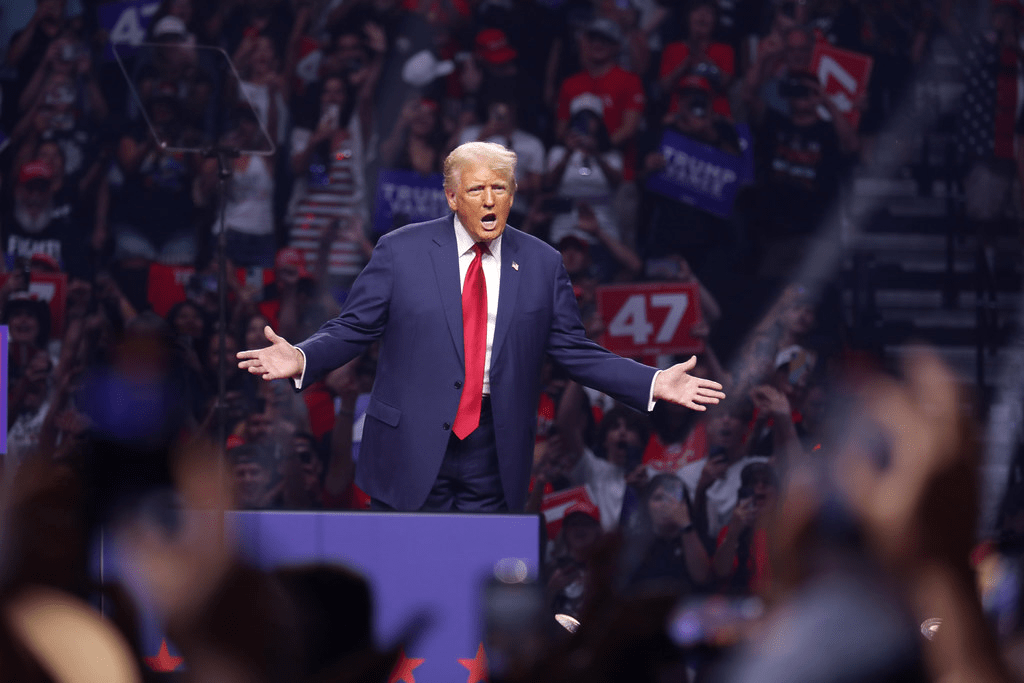

The hottest topic in fascist studies at this moment is undoubtedly the political movement and policy of Donald Trump, the most visible and archetypal figure of the contemporary wave of far-right populist movements across the globe. In most of the post-World War II era, the term “fascism” has been hotly debated, rarely applied to any contemporary movement or ideology. That reticence is a combination of its heavy associations and the real danger of devaluing the word into a commonplace insult. The reluctance to invoke “fascism” as a characterization of modern political phenomena has begun to recede over the past decade, particularly in reference to Donald Trump.

During his 2016 presidential run and early in his first term, Trump was characterized as a “fascist-lite,” a figure who blended neoconservatism with the use of fascist rhetoric. Most prominent political figures resisted the label itself, however. Madeleine Albright, Secretary of State under former President Bill Clinton, criticized Trump, referring to him in general terms as “antidemocratic,” not fascist, yet raising the possibility of fascism arising in the future. Trump’s attempted reversal of the 2020 presidential election results—in which he was denied re-election—and the spectacle of political violence that followed on January 6 prompted wider acceptance of the comparison. Fascism as a descriptor of Trumpism grew closer and closer to a mainstream position among the left and center-left during the 2024 election and its aftermath. It was encouraged by the increasingly violent, racialist tone of Trump’s campaign rhetoric, alongside liberal anxieties over blueprints for stronger political control such as Project 2025. By election day, Trump’s opponent, Vice President Kamala Harris, and his former top general, Mark Milley, had both characterized Trump as a fascist.

Even setting aside individual assessments of Trump as a fascist, the Trumpist movement, or MAGA (Make America Great Again), shares enough features with the classic fascist movements of the 1920s and 1930s to be described as a manifestation of fascism. Trumpism, like fascism, is predicated on emotional and instinctual mobilization, with simple exhortations to immediate, visible solutions (“Build the Wall!”) that defy and even mock liberal and conservative technocracy and rational government. Trumpism is driven by a charismatic leader, who, though not invoking a metaphysical identification with the historic destiny of the nation as did Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, positions himself as the one who “alone can fix it.” Both are reactions to crises of liberalism and a sense that traditional, respectable politics have failed the nation.

Hostility to intellectualism, identified with an elite scientific establishment, useless and dangerously radical humanities departments, and rejection of COVID-19 and climate change research as outcomes of conspiracies, is a hallmark of MAGA that echoes the anti-intellectualism in Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy. Most importantly, both Trumpism and fascism make use of violent rhetoric directed at internal enemies, or as put in Trump’s description in a Pentagon meeting, “the enemy within.” Add to that dehumanization, such as referring to internal enemies, particularly minorities, as “vermin” (a term employed both by Trump and Hitler), and a call for nationalist palingenesis, or rebirth, a term from pre-eminent fascism scholar Roger Griffin’s “minimum” definition of fascism. The list goes on, and I have not exhausted it here.

Yet, if Trumpism is a form of 21st century fascism, it is by necessity a far different and, for now, less extreme manifestation. Classical fascism emerged in the interwar years, achieving its fullest radical expression during World War II, and any discussion of fascism’s development must take into account its historical particularism. That is to say, if a new phenomenon develops today that shares the core features of fascism, it cannot be expected to appear like 1930s fascism nor to fulfill every element of it exactly, due to the different time period in which it originates. Trumpism in particular emerged not only from a 21st century movement but from an American one and thus is even more different in its conditions and expression than classical fascism.

The first wave of fascism grew out of a crisis of liberalism, which could not respond effectively to the social and economic crises that emerged in the wake of the First World War. Liberalism had been discredited by the conflict itself, which had subjected a nominally “civilized” Europe to carnage and death on a continental scale. The weak parliamentary governments of Weimar Germany and the Kingdom of Italy were paralyzed by deadlock and inaction in the face of mounting inflation, partisan violence, and strikes. The notion of national humiliation (an emasculating defeat in Germany and a “mutilated victory” in Italy) was compounded by the poor conditions of each country and the weak states that failed to improve them. These factors, combined with a desensitization to violence resulting from the war and its subsequent upheaval, were indispensable in giving rise to classical fascism. Disillusionment and trauma, in short, produced a crisis of liberalism that fascism aimed to resolve.

No individual crisis of liberalism as dramatic and earth-shattering as that of the First World War, which without hyperbole destroyed the pre-modern image of the world, is to blame for the global far-right movements emerging today. Mounting dissatisfaction with the inefficacy of the pre-Trump political system can be traced to a mix of “crises,” some less visible and dramatic than others, which Trump himself rhetorically synthesized into an ongoing “American Carnage” in his 2017 inaugural speech. A national economic disillusionment can be traced back to the institutionalization of neoliberal policies in the early 1980s and the subsequent growth of wealth inequality. Furthermore, the lingering effects of the Great Recession, itself an economic and emotional trauma, constitute a chronic, silent crisis for the liberal economic consensus of the past forty years. More than anything else, the 2008 recession served to deepen resentment of economic elites and their associations with liberal, moderate governance. Traumatic health crises, like the opioid epidemic or, more conspicuously, the COVID-19 pandemic, have also quietly affected American communities. The muffled emotional response to mass death and disability, not to mention the social rupture of COVID quarantine, may well be finding an expression in a darker-tinged political populism.

More visible crises have included the War on Terror and the border crisis with Mexico. Another national trauma, the September 11 attacks, was followed by a paranoia of external enemies, prompting civil liberty violations that set a precedent for authoritarian measures. The next two decades were dominated by two forever wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, which simultaneously tested popular patience with the nation’s foreign interventionism, exposed hundreds of thousands of Americans to war, and catalyzed a cult of the military.

The question of immigration across the Mexican border contains a number of perceived crises. One is a public health and safety crisis: a fear, further stoked by Trump himself, of illegal immigrants bringing crime and drugs into the country. Another is an abstract crisis of national sovereignty, violated in the national imagination by an amorphous open border and lack of control. Finally, there is a cultural crisis: an unspoken fear of white, Anglophone American culture becoming diluted and “Latinized,” for lack of a better term. Consider the MAGA reaction to Bad Bunny, born and raised in an American territory, performing at the Super Bowl as proof that the worry goes deeper than legalistic concerns over safety and sovereignty. The inability or reluctance of the state to respond to the aforementioned crises, and their role in creating them, has been an ally to the Trump movement. A softer, more heterogeneous crisis (or group of crises) of liberalism does exist, born not from one traumatic, visible cause, but multiple smaller ones.

Of course, one of the greatest allies of classical fascism was a fear of one crisis in particular: the threat of the left. In Weimar Germany, the 1919 communist uprising served as a basis for the fears of a communist takeover that eventually grew the Nazi ranks and convinced the conservative elites to hand power to them. In Italy, Mussolini’s squadristi received much elite support for their suppression of the strike wave across Italy and protection of private property. If we attempt to relate the same context to the circumstances that strengthened Trumpism, a major difference becomes apparent, which is the absence of an organized, revolutionary left to play on fears of. There is no worry about, or even capacity for, the kind of nationwide strike that drove frightened Italians, their capital, and their opinion into the arms of the Blackshirts. Labor in America is no threat to property or public safety, and it would be impossible to spin it that way.

Instead, Trumpism manufactures a threat from the left, or rather exaggerates the scope, organizational cohesion, and violent threat of various left-leaning movements, collated into the catch-all boogeyman organization “Antifa.” Sporadic images of chaos and violence have been amplified to substantiate this threat, more recently the assassination of Charlie Kirk, and, prior to that, the images of rioting and looting in the wake of George Floyd’s death. Fear of an external threat, namely Islamic terrorism, was mobilized to fearmonger about the disruptive 2024 protests against the Gaza genocide. Of course, one cannot discount the culture war in provoking fears about the left. “Gender ideology,” multiculturalism, and secularism are exaggerated and cherry-picked in their more extreme rhetorical manifestations to support the idea that a leftist cultural program threatens the traditional base of society.

The differences that inhibit a full-throated condemnation of Trumpism have not been exhausted in this article, but it is clear that MAGA’s propulsion by a crisis of liberalism is a solidly 21st century iteration of, at the very least, right-wing populism. The similarities to fascism are still broadly present, yet the specific conditions and historical memory of our time and place ensure that any contemporary American fascism will look very different from pre-war movements.

Categories: Domestic Affairs

1 reply »