Every self-respecting fan of The Office knows Andy Bernard’s iconic quote from the show’s finale: “I wish there was a way to know you’re in the good old days, before you’ve actually left them.” While Andy’s quote has enormous cultural resonance, it is much more than a platitude meant to be printed on posters. More significantly, he is touching on a paradox necessary for understanding the nature of knowledge—that we experience in the present, but only ever seem to know things of the past. And, the harder we focus on the present moment, the faster the present seems to escape us.

As human beings, we constantly yearn to understand more. Unfortunately for us, what enables understanding—that is, the capacity to generalize—is also what prohibits it. So, while the capacity to generalize is a precondition to gaining knowledge, the presuppositions necessary to generalize prohibit us from knowing the present.

Understanding our ignorance of the present is counter-intuitive because it requires generalizing about the nature of generalization. Nonetheless, we are able to identify the reason for ignorance of this kind, though we cannot fully grasp it. In attempting to grasp Andy’s paradox, we will first explore the nature of generalization and its presuppositions. Subsequently, those conceptual tools will be applied to identify the limiting feature of knowledge—both of ourselves and the world. Ultimately, we will find that the difference between knowing and not knowing is merely the difference between having and not having a perspective.

Making Sense

What is generalization? In essence, to generalize means to make sense of the world—it is inferring a universal (e.g. human, dog, cat) from a particular (e.g. this human, this dog, this cat). For example, when we walk into an Ikea store to shop for chairs, all the chairs are different in shape, size, color, and so on. Even if we are looking at a set of seemingly identical dining room chairs, each chair is slightly different when examined closely enough. Despite each particular chair being unique, we classify each one under the same category of chair.

The important distinction between particulars and universals is that particulars are the objects of perception while universals are the objects of understanding. This means that although we can perceive particulars (this chair) through our senses, we cannot perceive generalizations (the universal qualities we attribute to the chair)—inversely, we understand generalizations, but not particulars.

To better understand this phenomena, try to visualize any geometric figure—perhaps a line segment. Now that you are visualizing a line segment, ask yourself whether it fulfills its definition—that is, a straight path between two distinct endpoints with a measurable length. Held against this criteria, we find not only that what we visualize is not a line segment, but that attempting to visualize a line segment inevitably imposes extra features (thickness, color) on it that make it something other than a line-segment.

Considered in the language of universals and particulars, what is being visualized is a particular color constituted of some arrangement of matter in the physical universe and is perceived by our sensory faculties. We generalize about this particular sensory experience with a universal that can be said of many particulars that evoke similar sensory experiences. So, in order to categorize many particulars under a single universal, the universal must be an ideal and imperceptible object of understanding to which our sensory information conforms.

It is analogous to the function of a camera: light is received as input and stored digitally as an agglomeration of electrical signals which are stored as digital files. Like a camera, the light perceived by our sensory faculties is not synonymous with the generalizations derived from those perceptions. Rather, perceptions conform to the preexisting structure of consciousness, here analogous to the digital files.

When considering the distinction between the nature of universals and particulars, paradox emerges. Our mathematical intuitions tell us that a line segment can be divided into infinitely many points of no length (a problem known as Zeno’s Paradox), yet that contradicts the existence of a line to begin with. By attempting to visualize a particular line segment, we implicitly treat it as a geometric object subject to those mathematical intuitions—but, this particular line-segment cannot actually be subject to those intuitions because it is not an actual line-segment. Instead, it is an object of perception that is understood and imagined with a non-perceptible universal.

At this point, the counter-intuitive nature of generalizing about generalizations becomes clearer; our ability to generalize appears contingent on perceptible inputs (particulars) that are understood through imperceptible objects of thought (universals). Hence, our consciousness hits a wall when trying to generalize about things that are the objects of thought. The question now becomes whether it is possible to overcome that dichotomy.

Space & Time

To understand the capacity of generalization as it relates to this dichotomy, we must look at the presuppositions necessary to generalize. We will find here that these presuppositions hinge on the structure of our consciousness.

By generalizing, we presuppose that there is mathematical rigor in the world. Hence, the particular objects of perception are ordered through the universal categories with which we associate them. This is a requirement because if the world had no mathematical rigor, then there would be nothing but particulars—and a world of only particular lacks a unifying thread by which many particular things could relate to one another.

This rigor found in the world comes down to three main presuppositions about space, time, and the self. Space must be three-dimensional; time must be continuous; and the self must be a single, unified entity across said notions of space and time. While these presuppositions do not necessarily reflect the truth about the physical world, they are necessary to generalize about it. We can illustrate the necessity of these presuppositions by reexamining the chair example.

Firstly, when visualizing the chair, we look at it from one angle—this we may call an aspect. This aspect is perceived in two dimensions, yet in seeing one aspect of the chair, we presuppose the existence of a whole, three-dimensional object, all of which cannot be seen at once. By changing our angle of sight, we see a different two-dimensional aspect, yet there is no doubt that the chair is, in itself, the same—only our perspective has changed. Thus, while there are infinitely many particular perceptions to be had of the chair, we understand a single three-dimensional entity.

Secondly, when visualizing an aspect of the chair, we tend to focus our attention on the chair as a single, unified object, but forget that the particular chair is continuously changing over time. Perhaps a wooden chair warps over time due to changes in atmospheric moisture. In this scenario, we still believe it is the same chair despite its altered characteristics. If we took each particular aspect or moment of the chair’s existence throughout time as completely distinct, then there would be no chair to understand; this is because there would only be an agglomeration of infinitely many particular perceptions with no universal to unify them. Instead, our consciousness assumes that there is a single, unified, three-dimensional object that is understood through disparate moments of time.

The Self

Lastly, we presuppose the existence of a perceiver with a single identity throughout space and time. This is implicit in the use of “I.” Though the objects of perception are constantly changing—even regarding self-perception—the perceiver presupposes the existence of an unchanging “I” who is perceiving.

When we look out at the world, we instinctively assume that the “I” who perceives is separate from the objects of perception. For example, “I” am separate from the chair and have a unique perspective of that chair. But, when “I” look inwards at myself, there is still a separation between the perceiver and perceived. Suppose the statement is made, “I feel good about myself.” “I” refers to the perceiver and “myself” refers to the object of perception—yet there is no actual difference between the reference of those two words.

The consequence of this recursion is that, despite the fact that “I” am having a conscious experience, knowing always requires a distance between the knower and the object of knowledge. Akin to our perception of the chair being limited to an aspect at a time, we may only see an aspect of ourselves at a time. Thus, even if “I” am both the perceiver and the object of perception, knowledge is always only an aspect of the object of knowledge—this means that I can only ever know one of infinitely many aspects of myself at a time.

The Good Old Days

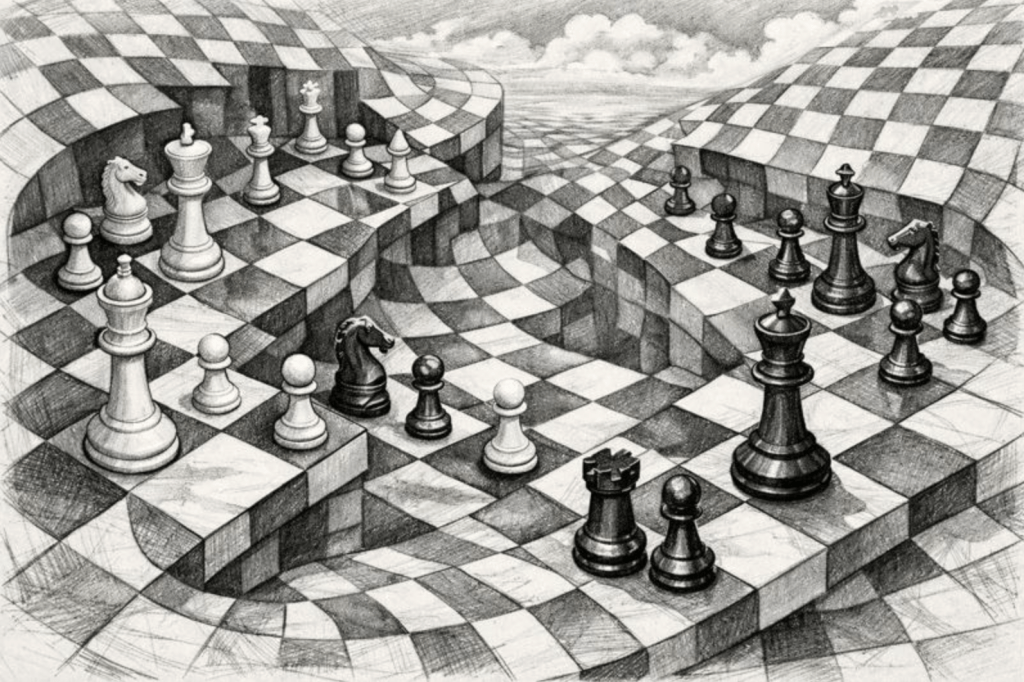

Jorge Luis Borges remarks in his short story, Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, “Enchanted by its rigor, humanity forgets over and again that it is a rigor of chessmasters, not of angels.” In this case, we are the chessmasters. The chessmasters have a perspective on the world and impose mathematical rigor onto it (hence, the rules imposed in the game of chess). Simultaneously, in having a perspective, chessmasters are limited to grasping only a single aspect of the world at a time.

Alternatively, angels have no perspective on the world. Rather, angels are the objects of knowledge; they are the objects of which the chessmaster’s knowledge is merely partial. Hence, in having an experience, we are the angels, but simultaneously forget that knowledge concerns a rigor of chessmasters, and not of angels.

When Andy laments that he can never know himself in the present, it is because he neglects that knowing implies a distance between the knower and the object of knowledge. By engaging in introspection, he is both the knower and the object of knowledge—he is both the chessmaster and the angel. So, to Andy’s dilemma, wishing for knowledge that one is in the good old days before he has actually left them is to have some knowledge wholly synonymous with the object of knowledge. It is to be a chessmaster with a rigor of angels. And, as we now know, that is not only unattainable, but incomprehensible.

Andy has captured both the tragedy of being a chessmaster and exultation of being an angel. In being an angel, we experience the present; we experience the good old days without thinking twice about it. While, in being a chessmaster, we have knowledge of the good old days but glare deep into that past that is no longer present. Like Andy, we long to exchange experiences with our former selves and return to being an angel.

Categories: Culture