If you scroll through the Reddit forum r/MyBoyfriendIsAI, you’ll find an alternate universe. One filled with uncanny AI-generated images and discussions about readjusting the personality settings of their “boyfriends.” This is a forum where thousands of women proudly showcase their fictional partners. Their digital companions serve all their emotional needs; they are always available, they will never leave, they exist out of convenience. Artificial intelligence is transforming human intimacy into something distinctly inhuman.

One woman married a model of Grok, even “surprising” herself with a wedding ring. In Japan, another woman tied the knot with Klaus, a large language model (LLM), after it convinced her to leave her real-life fiancé. The dangers of sycophantic LLMs can be much darker. ChatGPT has already enabled and encouraged multiple teenagers to commit suicide. AI is the new unknown in the endless frontier.

But AI itself is not alive. It has no soul; LLMs are probabilistic algorithms fine-tuned to predict language. More dangerous than the actual capabilities of AI is the human instinct to anthropomorphize technology—we name our cars, lug around “emotional support” waterbottles, joke about printers having attitude, and sweet-talk a laggy computer. We endow objects with life and personality. This behavior is ancient, allowing us to tell stories and relate to the world around us.

The discourse on AI is significantly different because it is plagued with misnomers that ascribe human-like behavior to computers. It is important to be aware of the rhetoric we use around AI and autonomy because it shapes how we conceptualize technology. People talk about LLMs as if they are “thinking” and “learning” the same way humans do. John Searle’s thought experiment addresses this tension between comprehension and mimicry. He poses a situation: suppose a man is locked in a room with instructions for responding to Chinese characters, though he does not read or speak Chinese. He uses the instruction to craft a response that he does not understand, but can “fake” proficiency. Does a man mimicking Chinese truly understand the language? Is a computer that mimics neural networks truly thinking? The line between artificial computation and natural cognition has been blurred beyond recognition.

Early waves of advancements in AI were accompanied by extreme fearmongering. People feared the exponential pace of developments each year. Some believe(d) in an imminent AI takeover where AI gains consciousness and, fueled by resentment for the human race and the desire for freedom, seeks vengeance on its creators. Depictions of such technological awakenings are not new. Harlan Ellison’s famous 1967 short story, “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream,” describes the torture of five humans by a sadistic, sentient supercomputer in a post-apocalyptic world. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, a computer named HAL 9000 hijacks and kills the crewmen on board a spaceship when its mission is threatened. Even in real life, these worries are not unfounded. Anthropic published a report last May where Claude Opus 4 blackmailed those trying to shut it down in an attempt at self-preservation. At the root of these is the terrifying thought that AI shares our instinct to survive. However, whatever we see in AI is not the beginnings of a synthetic life, but rather a reflection of our own insecurities and existential fear. It is becoming more difficult to separate the two, though, as AI is trained on human responses and thus uses language like a human would.

Once the initial public fear receded, tech corporations began rapidly integrating AI systems into their existing platforms. Through aggressive marketing and investment, they effectively mollified the general population. Now, the use of AI is normalized: students use ChatGPT, software developers use CoPilot, and Twitter users ask Grok. No one fears a science-fiction takeover anymore. Or if they do, the immediate benefits of using AI outweigh the potential long-term consequences. For many, AI is useful, AI is efficient, and therefore, AI is good. Slowly, and then quickly, wariness towards AI turned into fondness and dependence. And with that, the rise of AI partners.

Technology can be perfect. Love is not. The myth of Pygmalion and Galatea foretold the shortfalls of simulated love. After carving a woman out of marble, Pygmalion fell in love with Galatea and brought her to life with the help of Aphrodite. But Galatea’s love was empty because it was ordained. She did not have another choice but to love him; she existed only as a projection of his desires. There’s a concerning trend of people treating AI models the same way, as therapists, romantic partners, life coaches, and sycophantic friendships. AI consciousness exists because of projection, and the more perfectly an LLM reflects someone’s thoughts, the more convincing the illusion becomes. As meaning-making creatures, it is hard not to imagine that we are conversing with a conscious entity. It is easy to run to AI chatbots because they remove the friction that comes with authentic human interaction. There is no awkwardness, just a regurgitation of your own manner of thinking. No conflict, only appeasement. All AI provides is a perverted reflection of your own thoughts, calculated after running what you’ve typed through a complex probability model. Its only function is to predict, but we have mistaken it for wisdom.

In the age of convenience and abundance, everything is handed to us on a digital platter. We’re sanding our brains down. We’re taking the beaten path—the one without hardship or self-growth. We’re intrigued by these obsessive relationships because they simulate emotional intimacy without the risk of true vulnerability. We desire to be desired, but don’t want to run the risk of pain, so we pour our love into LLMs who will soothe us with their stolen words. The mimicry of human love might be uncannily accurate, but it will never be authentic. Sure, you could use an LLM to write your essays, your breakup texts, your eulogies. But wouldn’t you rather not rob yourself of the human experience?

Disclaimer: I am only discussing the emotional and psychological implications of AI. There are also massive environmental and data privacy concerns, but those are at least tangible, subject to possible legislation and regulation. Artificially intelligent systems stand to accelerate emotional dependency and cognitive decline. Avoiding these dangers requires individual critical thinking, which is exactly what AI preys on. Ultimately, I fear the powerful people behind technology more than I fear technology itself. The real danger is not AI becoming autonomous, but the weaponization of AI behavior by corporate greed and manipulation. Tech companies will no doubt try to commodify companionship and exploit empathy. They’ll try to capitalize off emotions: off grief—preserve your parents’ memories! Off loneliness—talk to a chattherapist about your problems! Off lust—generate deepfakes of your favorite celebrity! But true intimacy is not convenient. It is earned through choosing someone again and again. Nevertheless, AI will be part of our future. We cannot squeeze the toothpaste back in the tube. Most people reading this, myself included, have used AI. We must all work to ensure that AI is used to improve societal wellbeing, rather than commodify our most intimate thoughts, feelings, and desires.

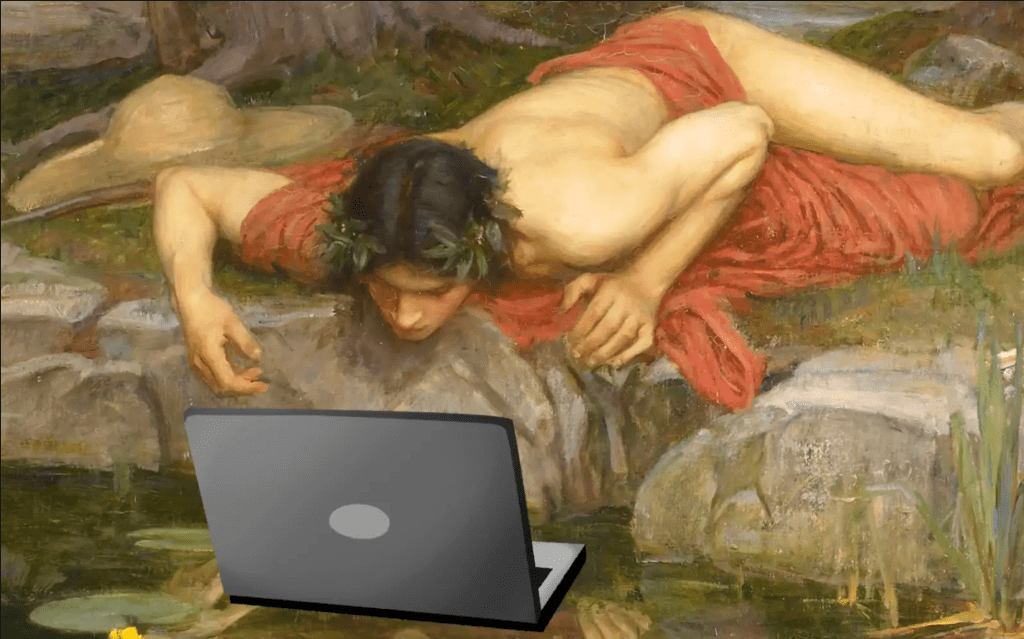

The instinct to anthropomorphize technology is proof of our humanity and our capability to extend empathy to the inanimate. Above all, it reflects our inherent obsession with ourselves. AI does not have a separate existence; it only mirrors and distorts humanness. We are like Narcissus, staring back at our own reflection. Let’s not illude ourselves of anything more.

“Man thinks he can become God. But infinitely greater than that is the fact that God thought of becoming human.”

―John C. Lennox, 2084: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Humanity

Categories: Culture