Introduction:

Can artificial intelligence develop the same moral agency as human beings? In order to answer this question, we have to consider two things: the definition and determinants of moral agency. Across the literature, moral agency is defined as the ability to discern right from wrong and apply normative frameworks to our decisions. This agency has three main determinants: self-awareness, stimuli responses, and stimuli reception [1]. This article will first examine the contributions of self-awareness and stimuli responses to moral agency in humans and AI — specifically from the film 2001: A Space Odyssey and novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? — before considering stimuli reception. Based on these examinations, I argue that AI does not possess the same moral agency as humans, as it lacks the biological basis for self-awareness, simulates rather than produces moral responses, and lacks the necessary cognition for complex stimuli processing.

Self-Awareness and Stimuli Responses in Moral Agency:

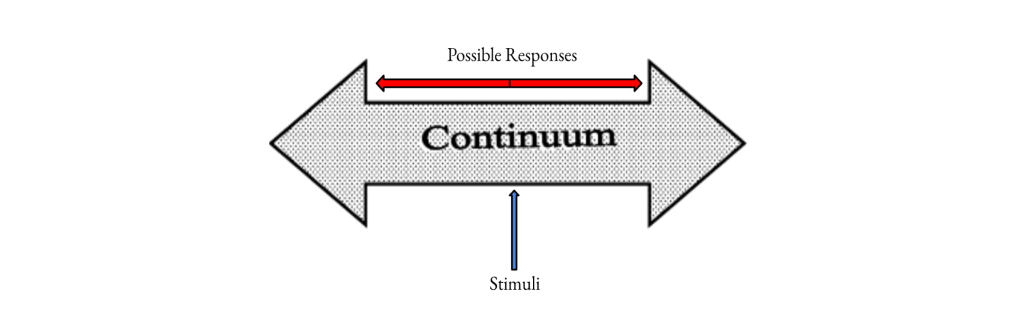

The neurons in our brains evolved over thousands of years. Eventually, they came together to form regulatory networks that could process stimuli and communicate with each other. The thalamus, for instance, receives a stimulus and relays it to the cortex for processing. The cortex, then, not only returns signals to the thalamus, but also communicates with the brain’s temporoparietal region to induce interoception, an awareness of one’s physical state. Through this awareness, humans are able to function beyond instinctual behavior and exhibit responses that fall along a continuum of near infinite possibilities; slight changes in stimuli could elicit entirely different reactions. In this sense, human interactions with the world are more diverse [2].

Along this continuum, humans tend towards more ‘rational’ responses. Why? Because as physical beings, our interests naturally lie in self-preservation. Early in our evolution, mankind mingled and warred in a very primitive, aggressive sense — explained less by layered, geopolitical motivations, and more by immediate physical confrontation. But behaviors that promoted cooperation and reduced conflict were naturally selected for. Over time, a gradual, integrative process occurred [3]. Humans developed higher-order cognition and ethical reasoning capacities. We began functioning as moral agents who were expected to discern right from wrong, and began deploying legal systems to enforce those moral discernments [i.e. murder, theft, rape, etc]. Now, set within a moral framework that encouraged rational responses along the continuum, humans could ensure a more pleasant way of life. But, couldn’t AI do this as well? Couldn’t they make logical deductions and act accordingly? In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep by Phillip K. Dick, for instance, advanced humanoids called replicants are genetically-engineered to exhibit a desire to live and show some semblance of emotions. What’s more, they react to their treatment as subhuman slaves. So perhaps they, much like us, must operate on a right-wrong basis, as they realize slavery is bad.

Indeed, they appear as moral agents that can discern right from wrong. But that doesn’t mean they are moral agents the same way humans are. The reason why is because while replicants might be functional equivalents to humans, they aren’t necessarily ontological equivalents [4]. Even if they respond like humans, that doesn’t mean they are humans — if A [awareness] → B [varied responses] → C [moral agency] in humans, just because the replicants possess C doesn’t mean it arose through A and B. Specifically, these humanoids aren’t the products of natural selection; their genetic makeup is entirely designed by the Tyrell corporation. While they may simulate moral reasoning, they lack the awareness required to develop a continuum of responses. And without this continuum, moral agency cannot emerge organically. One has to experience the responses first before deciding which ones are most conducive to welfare, rather than just have everything pre-programmed into a body.

Stimuli Processing in Moral Agency:

Yet, moral agency isn’t just determined by awareness or our responses to stimuli — it also depends on how humans process stimuli in the first place. Real-life artificial intelligence, similar to the humanoid replicants, rely heavily on layered neural networks to acquire and process data. As computational models that imitate the biological structure of brains, these networks consist of interconnected nodes — artificial neurons — that process data layer-wise and can ‘learn’ by recursively adjusting their parameters to reconfigure their outputs — a process known as backpropagation [5]. The biological brain, however, is distinct. While neural networks use external algorithms to alter synaptic connections and reduce output error, neurons in organisms’ brains are optimally configured before their synaptic connections are adjusted — a phenomenon known as prospective configuration. The following example of a bear fishing for salmon explains this distinction:

Imagine a bear seeing a river. In the bear’s mind, the sight generates predictions of hearing water and smelling salmon. On that day, the bear indeed smelled the salmon but did not hear the water, perhaps due to an ear injury, and thus the bear needs to change its expectation related to the sound. Backpropagation would proceed… to reduce the weights on the path between the visual and auditory neurons… also entails a reduction of the weights between visual and olfactory neurons that would compromise the expectation of smelling the salmon the next time the river is visited, even though the smell of salmon was present and correctly predicted [6].

Evidently, backpropogation interferes with the memory of other similar associations. On the other hand, prospective configuration suggests that human brains are much more flexible in their reception of external stimuli, as it reduces interference by preserving existing knowledge and speeding up learning. This is foundational for moral agency, as it often requires weighing new information against established beliefs, values, and past experiences. Consider 2001: A Space Odyssey, for instance. HAL 9000, a heuristic AI computer, seemingly murders the astronauts aboard Discovery One, and yet he is not presented as a villain, but rather a cognitive system pushed to his breaking point. His actions—pure, recursive, unfeeling—emerged from a logical paradox between two conflicting directives: relay vital, life-saving information or withhold critical objectives. In choosing the latter, HAL demonstrated the limitations of AI processing: without the ability to organize overlapping layers of meaning [i.e. human lives over mission directives], he couldn’t reliably choose between right and wrong in a consistent, context-sensitive way.

Important Considerations:

However, there’s an aspect of moral agency that both humans and AI share: a ‘black box.’ The term refers to the idea that we know the stimuli and responses of a neural machine or brain, but the complex synapses that occur within extend far beyond what computational models or neuroscience can explain. For instance, in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, the Nexus-6 android Rachael Rosen exhibits behavior that suggests emotional depth and introspection, despite failing the Voight-Kampff test, which asked her a series of emotionally-charged questions to determine whether she was a replicant [she was]. This contradiction makes it harder to ascertain whether her apparent feelings are real or simply advanced simulations, and emphasizes this ‘black box’ dilemma, as internal processes — whether emotional, programmed, or both — remain opaque. In a sense then, this muddiness becomes problematic.

Metaphysically, if neither the human brain nor AI can be fully decoded, the value of our examinations diminishes. Traditional moral philosophy presupposes a rational agent making deliberate, reasoned choices—an agent whose intentions can be examined. But the black box complicates this assumption: neurological processes and machine learning algorithms generate outputs humans can observe but not always trace back to a clear, conscious rationale. And although we know that AI is explicitly created by us, we don’t truly understand our own origins. Because of this epistemic gap, the moral expectations humans place on AI systems seem increasingly difficult to reconcile with the reality of their design; after all, they reflect our own cognitive and moral limitations.

These limitations are especially evident in healthcare technologies. For instance, they make it harder to ensure that AI systems align with the principle of justice—ensuring fairness across all demographic groups—as humans don’t fully understand how they make decisions. Further, AI models are trained on large datasets, and if these datasets are incomplete or biased, the AI can mistakenly encourage socio-economically unfair outcomes [6]

Conclusion:

Duly then, AI does not possess the same moral agency as humans. It may simulate outward behaviour of moral agents, but it lacks the biological foundation of self-awareness and adaptive reasoning necessary for human moral agency. Self-awareness in humans arises from an evolutionary, embodied, and introspective process—a process that fosters nuanced responses along a continuum. AI, in contrast, simulates responses based on pre-programmed logic and backpropagation, unable to organically absorb ethical frameworks in the way humans do. However, we still do not know how humans and AIs fundamentally function, so it is important to tread carefully when imposing our beliefs onto vital AI systems in healthcare and society.

Categories: Culture