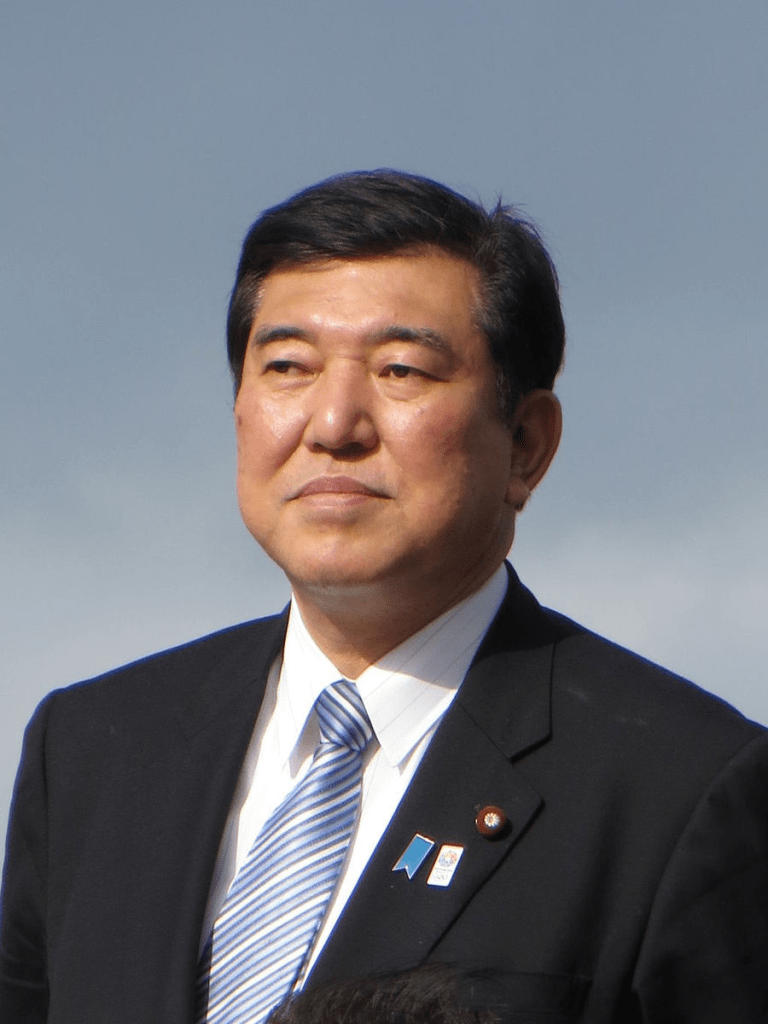

“Our country is facing the most severe and complex security environment of the post-war period,” warned newly elected Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba in his first policy speech addressing Japan’s legislature, the National Diet, on October 4.

Ishiba recently assumed office on October 1 after his predecessor Fumio Kishida stepped down amid numerous corruption scandals and low voter approval. Since the 1950s, the Japanese political landscape has been dominated by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) effectively creating a one-party system. However, public trust in the party essentially collapsed after corruption appeared associated with recent LDP administrations such as those of Fumio Kishida and Shinzo Abe. Scrambling to find substantial footing, the party opted for Ishiba as Kishida’s replacement.

Prime Minister Ishiba is seen as an outsider of the LDP after butting heads with Shinzo Abe, the long-time “face” of the party, in the 2010s. While many Japanese legislators gave up their integrity to blindly follow Shinzo Abe’s democratic backsliding, Ishiba (mostly) stood firm on his policies and avoided the corruption scandals that marred Abe’s administration. While initially labeled as a traitor to the party, Ishiba appears to be the ideal candidate at a time when the general Japanese populace feels disillusioned with the LDP.

Shigeru Ishiba’s platform is centered around bolstering the rural economy, combatting Japan’s declining birth rate, and strengthening Japan’s defensive capabilities. However, a snap general election held on October 27 resulted in the LDP losing its majority in the Lower House of the Diet, making these reforms much less likely to pass. This was a major blow to the Ishiba administration, as legislation that would have previously passed seamlessly through the House will now be blocked by the minority parties.

That being said, compromise with important figures in the Japanese legislature, such as the former Prime Minister and current leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) Yoshihiko Noda, could result in Ishiba being able to push at least some of his reforms through. One area in which Ishiba may be able to create reform is his plan to bolster Japan’s military capabilities. Japan is perhaps the United States’ most strategic ally in the Indo-Pacific, and Ishiba’s policies will benefit our security interests in the region. However, he must be careful that he doesn’t become too radical in his policies, as this would most definitely lead to endless legislative gridlock and a short, ineffective term.

Ishiba is a self-proclaimed “Gunji Otaku,” or military geek. Simply put, he loves all things having to do with military strategy. The new Japanese PM believes strongly in building a robust collective security sphere with Japan’s valuable allies in the Indo-Pacific. This is evidenced by the fact that within hours of taking office, Ishiba called Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol to discuss bilateral security cooperation against the nuclear threat posed by North Korea. Ishiba cited South Korea as an integral Japanese partner in the region, prioritizing the cultivation of much smoother bilateral ties than those with Korea under Shinzo Abe and other former administrations.

In addition, the Japanese PM has cited Taiwan as a key locus for maintaining collective security in the Indo-Pacific. In a rapidly shifting global security environment, Ishiba views Taiwan as a strategic ally to Japan; if it were to fall, Japan could be next.

Ishiba warned the National Diet that “Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow.” Like many international observers, Ishiba believes that Russia was only able to invade Ukraine because it was outside NATO’s collective security bloc. If Ukraine had been a member of NATO, then the potential invocation of Article 5 of the Washington Treaty could have been enough to deter a Russian invasion. Similarly, because Taiwan is not a member of any collective security agreement, Ishiba believes there aren’t substantial mechanisms to deter China from invading Taiwan in the future. However, Ishiba posits that this lack of deterrence could be resolved if Japan and its allies created a collective security agreement similar to NATO.

Termed an “Asian NATO,” Ishiba’s proposal would include all of the United States’ strategic allies in the Indo-Pacific, as well as integral members of ASEAN. The framework is structured in a hub-and-spoke system in which the United States-Japanese alliance is at the center, while other members are linked to this core bilateral partnership. Moreover, Ishiba proposed that the United States share nuclear capabilities with Japan to safeguard against potential attacks from antagonistic states in the region that also possess nuclear weapons. This elevated partnership thereby would leverage Japan as a regional power by substantially enhancing its militaristic presence to an extent not seen since WWII.

However, the plan for an Asian NATO has already fallen short due to several factors. First, the key partner in the agreement, the United States, isn’t even on board with Ishiba’s plan, describing it as “hasty.” The fact of the matter is that the United States is quite pleased with its current position in the Indo-Pacific, or at least content enough not to enter a high-stakes multilateral pact such as that proposed by Ishiba.

Moreover, the Japanese public isn’t keen on joining a collective security agreement that may result in the Japanese military having to engage with China. In a recent survey, only 11% of Japanese respondents were willing to enter an agreement in which they may be forced to protect Taiwan. Ishiba must listen closely to the public’s opinions as longevity in the Japanese executive is highly dependent on public support.

Japanese political culture values the greater good of the population over that of the individual, therefore it is common for Japanese prime ministers to step down due to overall dissatisfaction with their performances. The position of the Japanese Prime Minister is quite volatile in the sense that there is no set term limit; one essentially serves until one loses the confidence of the House or the citizens. For example, former PM Yoshihide Suga’s cabinet’s approval rating was 62% at the beginning of his tenure in September 2020, yet dropped to 30% by October 2021, causing the LDP to force his resignation. Ishiba has already come into office with one of the lowest initial approval ratings, at just 51%. Therefore, he can’t risk pursuing foreign policies that lack public backing, or else he may be forced to resign quite early before being able to redirect the path of the declining LDP. Ishiba can internally change the party, distancing it from a party marred by corruption and economic decline to one that will elevate Japan to a true military and economic power.

Additionally, Ishiba’s vision for a collective security agreement is not even viable under Article 9 of the current Japanese Constitution, which states that “the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.” In short, Japan is prohibited from engaging in any offensive military campaign. While a Chinese invasion may appear to warrant a retaliatory Japanese attack, the Japanese still consider this to be an offensive military engagement. The Japanese Constitution infers that the country’s military should only be used to defend an attack on Japanese soil.

Former PM Shinzo Abe attempted to amend Article 9 of the Constitution to increase the offensive capabilities of the Japanese Army, otherwise known as the Self-Defense Forces (SDF). Despite his efforts to do so, the attempts at reform fell short due to high levels of public opposition. According to LDP lawmaker Hajime Funada, “[f]or the Japanese people, Article 9 is a kind of Bible.” The Japanese are content with their pacifist role in the post-war era, which includes being a proponent of human security and global economic development rather than military intervention. Fortunately, since the LDP lost their supermajority in the House, Ishiba and the numerous nationalists in the Japanese Legislature are unable to launch another attempt to amend Article 9 of the Constitution. Fruitless attempts to do so would not bode well with the Japanese people and would likely force the PM to resign instead. As aforementioned, Ishiba can elevate Japanese foreign policy with a long enough term. His concept of an Asian NATO should be tabled and only enacted if Japan’s strategic allies and citizens are fully on board.

Instead, Ishiba should focus on bolstering Japan’s bilateral alliances with the United States and other strategic partners. While a formal collective security pact is not viable, focusing on building a “latticework” of bilateral or trilateral agreements will be integral for the prosperity and security of the East Asian nation.

That being said, Ishiba will still have room to be slightly bullish in his foreign policy posture as demonstrated in his attempts to create a more equal partnership with the United States, mirroring the relationship between the United States and the United Kingdom. The Japanese Prime Minister has already argued for revisions to the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty and the Japan-U.S. Status of Force Agreement (SOFA) which he deemed “asymmetrical.” Some potential reforms include joint management of the United States’ bases in Japan, stationing of Japanese troops on the U.S. overseas territory of Guam, and increasing joint military exercises between the two countries. All of these reforms are designed to create a more co-dependent relationship between the two countries in the Indo-Pacific without resorting to a collective security agreement with the powder keg that is Taiwan. Thus, these reforms are beneficial for Japan in terms of enhancing its military capabilities and partnerships while not violating Article 9 of its Constitution.

In the end, working on bilateral and trilateral agreements with the United States, South Korea, and other strategic partners like the Philippines should be Ishiba’s priority in foreign relations. The Japanese people and the country’s strategic partners aren’t quite ready for a commitment to an Asian NATO. The “Gunji Otaku” is indeed an ambitious nationalist. Still, he may need to curtail some of his policies if he wants to successfully bolster Japan’s security in the Indo-Pacific region and reconstruct the LDP and Japanese domestic policy.

Categories: Foreign Affairs