Are you installing a new monument? Are you the recipient of funds from a non-governmental organization, foundation, or the state? Do you want to start a little controversy in your neighborhood? If so, this guide is for you!

If you’ve traveled through Central Europe, you know it’s impossible to not stumble across a statue or monument commemorating victims of World War I, World War II, or the Cold War. There are also Baroque-era relics symbolizing the end of the plague or other artifacts dating back to before America was even an organized country. Back home, memorials in the U.S. may also honor victims of the world wars, but also portray victims (and perpetrators) of conflicts like the American Civil War.

At the end of the day, regardless of its era, a good memorial should accurately honor those who are represented. But what makes a memorial “good”? Here are the guidelines that anyone erecting a monument, statue, or art installation should consider.

DO: Put your monuments in easily accessible places.

Let’s start with an easy one. When constructing a monument, it’s vital that it will actually be seen. At the end of the twentieth century, the University of Texas unveiled a new statue memorializing Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., civil rights activist. It was actually only the second MLK statue at a university in the U.S. after Morehouse, the alma mater of Dr. King. It may seem like common sense to place monuments in accessible places, but you’d be surprised how many hidden or closed statues there are across the world.

The best part of UT’s statue: MLK is easily recognizable to anyone passing the East Mall on their way to Patton Hall (RLP) or the football stadium. A good memorial needs to be visible.

DON’T: Restrict them to academics.

Imagine finding a memorial that is supposed to represent something important but you have no idea what it’s saying. Frustrating, right? The Memorial Against War and Fascism in Vienna consists of four separate statues representing four different aspects of Austria’s role in WWII. From Atlas Obscura, there’s the “Gate of Violence” (made of granite from the Mauthausen concentration camp) to honor victims of Nazism, the “Street-washing Jew” to commemorate the Jewish people “forced to scrub the streets clean of pro-Austrian, anti-Nazi slogans as a form of humiliation and degradation,” the “Orpheus Enters Hades” to memorialize victims of bombings, and an excerpt from the Austrian Declaration of Independence engraved in granite.

Criticism number one: even though many things in Vienna are bilingual, from the people to restaurant menus to the U-Bahn, a majority of this memorial is only in German. When tourists and scholars alike try to take in the history of Vienna, how will they know what they are looking at?

Criticism number two: neither the Street-washing Jew nor the Orpheus statue have plaques explaining their significance.

And criticism number three: prior to the artist adding spikes in the late 90s, people would sit to rest on the Street-washing Jew because they simply did not know what it represented. If a monument only means something to scholars or those who did their research prior, it isn’t efficient or effective. Granted, the memorial is in a great spot physically – its home on Albertinaplatz is directly downtown and near well-known tourist attractions. But what does that matter if nobody knows what is being portrayed?

A good memorial needs to be academically as well as physically accessible.

DO: Keep in mind the victims of atrocities, but…

DON’T: Remember them in an offensive way.

Constructed overnight to avoid protest, Budapest’s memorial dedicated to “all of the victims” of the Holocaust portrays the angel Gabriel – a Christian symbol and stand-in for Hungary – and the German Imperial Eagle. The eagle is attacking Gabriel, symbolizing Nazi Germany “attacking” Hungary. Supporters of this monument cite that it’s necessary for Hungary to reckon with the horrors of the Holocaust, especially since part of it happened right on their doorstep.

But what about the Hungarians who, under occupation by the Third Reich, complied with or even supported the Nazi regime? And why, when the Holocaust mainly impacted Jewish people in Europe, does the monument memorialize a Christian angel? According to critics, the memorial “absolves the Hungarian state and Hungarians of their active role in sending some 450,000 Jews to their deaths during the occupation.” Moreover, Hungarian politician Ferenc Gyurcsany accuses the memorial of dishonoring “all Jewish, Roma and gay victims of the Holocaust.”

A common issue throughout post-war Europe was assigning blame only to Germany when so many other countries were responsible. As a result, many of these countries struggle to accurately reckon with their role and honor the true victims of the war. According to the Smithsonian, “In the years since the Cold War, [Hungary] has fielded heavy criticism by Holocaust scholars who say the country is shifting from acknowledging that complicity to portraying itself as a helpless victim of Nazi occupation.”

A good memorial needs to recognize its political role in society and the creators need to acknowledge its cultural significance.

DO: Consider your wording.

As previously mentioned, European countries sometimes have a difficult time reckoning with their involvement in WWII. In fact, according to a 2023 survey, nearly a quarter of the Dutch believe that the collective memory of the Holocaust was greatly exaggerated or a myth. Big yikes. As a result of this reluctance, some European memorials greatly undercut who the perpetrators were. In Austria – which is former Third Reich territory – older monuments tend to skirt around the country’s role. The title “Vienna memorial to the victims of Fascism” is already inherently iffy – why not call it the “memorial for victims of the Holocaust” or “victims of anti-semitism”?

Moreover, it’s very clear that components of the statue were added as time passed by. A Star of David and a red triangle (symbolizing political prisoners), not originally part of the statue, are now housed at the top alongside the statue of a (fairly ambiguous) man. Is he a Jewish, gay, or Romani man? Who are they implying was the victim, and why did it take so long for this aspect of the statue? Then of course there is the location. This monument is housed not downtown but on top of a former Gestapo headquarters site – but that’s not the purpose of this section. Instead, we need to elaborate on the former point that there is an offensive way to remember victims, and this one might fall under that category.

Some Austrian folks today still believe the myth that they were victims of Nazism, not perpetrators. There’s even an academic term for this: the Austrian Victim Theory. At the same time, it has become more common for younger generations to realize that that simply isn’t true. Politically, it took until the 90s for Austria to publicly admit its complicity during WWII, and it’s very clear that this memorial reflects the decades of controversy and reluctance of the state to admit its true role.

A good memorial aptly recognizes the victims and is direct. It also allows for room to grow.

DON’T: Put contentious ones within reach of passersby. Or if you do, expect a response.

Back to America. Throughout 2019-2021, Christopher Columbus statues were vandalized in Boston, MA, Richmond, VA, and Providence and Westerly, RI. The statue in Providence sported “Stop Celebrating Genocide” and bright red paint.

The memorialization of Columbus is very controversial; for starters, he really didn’t discover America, as he landed in the Caribbean. Moreover, he enslaved and brutally tortured countless natives while in the New World. He also ushered in many European diseases that obliterated Native populations.

Throughout the 21st century, it has been politically accepted by many – including the United Nations and the White House, as of 2021 – to celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day rather than Columbus Day in October. So it’s no surprise that Columbus statues were defaced. Even if you think that perhaps red paint goes too far, I’ll remind you that even America’s most famous protestor, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., advocated for a bit of civil disobedience once in a while.

And guess what: the paint worked! In 2020, the mayor of Providence announced that the statue would be taken down until discussions could occur. Protests and contention can create change, and embracing this phenomenon ensures public opinion is protected and respected.

A good memorial creator anticipates how their memorial will be remembered.

DO: Allow for counter-monuments.

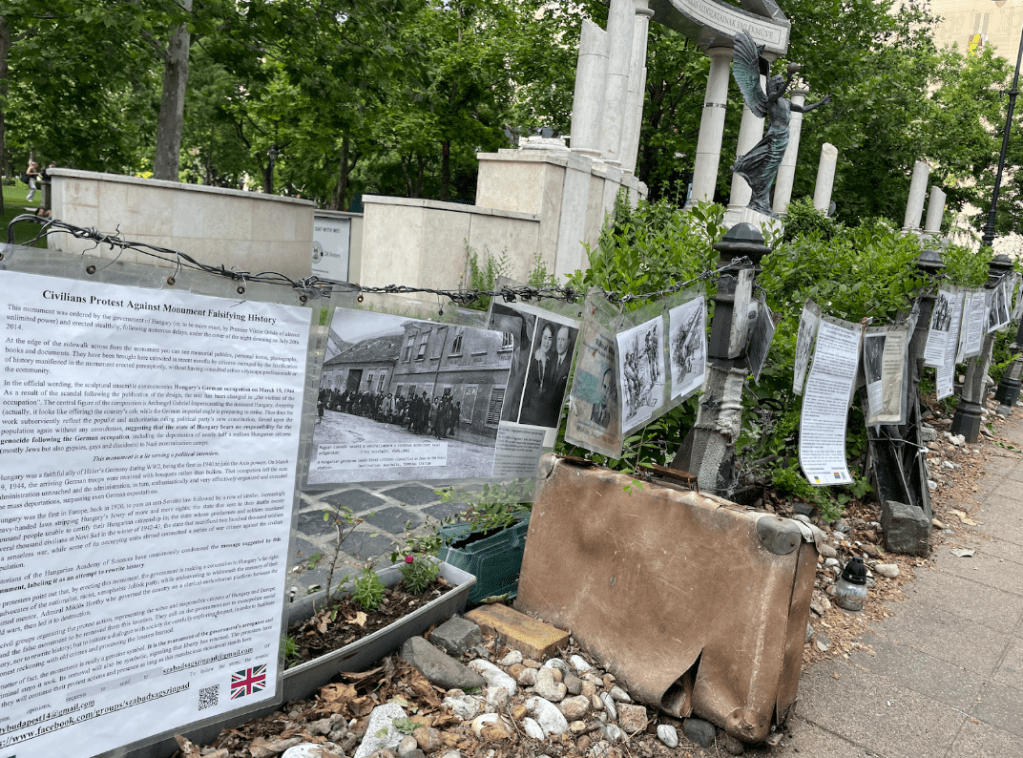

The WWII memorial in Budapest now hosts a multitude of informational sheets (in nearly every language conceivable) and artifacts and photos placed by descendants of Hungarian Holocaust victims.

These sheets read: “Civilians Protest Against Monuments Falsifying History… At the edge of the sidewalk across from the monument you can see memorial pebbles, personal items, photographs, books and documents. They have been brought here uninvited in recent months by citizens outraged by the falsification of history manifested in the monument erected peremptorily, without having consulted either cityscape professionals or the community… This monument is a lie serving a political intention.”

Powerful stuff. Just like in the States, freedom of speech and assembly are protected by Hungarian law – and what better way to take advantage of this freedom than in a very public setting? This all brings up a very important aspect of constructing any type of monument: we all, including the government, have the right to say what we want and must anticipate the backlash. Whether it’s a controversial memorial to victims of the Holocaust or a Christopher Columbus statue, a government must protect its citizens by ensuring the right to protest.

A good memorial reflects the vital state of freedom of speech, and the organizers need to as well. That being said, I now have the freedom of the press to say this:

DON’T: Idolize the bad guys.

This one feels repetitive after many of the previous ones, but for some reason, it still needs to be said. Running the risk of this article being banned in the state of Florida, I need to point out that the Confederate army not only lost the war but also, and this statement is backed by historians, supported the institution of slavery. Now that Ron DeSantis is knocking on my door, I need to quickly say that we shouldn’t memorialize Confederates! Yet, there is a big ol’ statue right down the street from UT at the Texas Capitol dedicated to the Texan soldiers – traitors – who supported secession in the 1860s. I’ll say nothing but refer back to the two previous points.

Oh, and let’s not forget that we are only a couple of years past having our own Confederate statues on campus. Why did it take until 2017 for that removal to happen?

A good memorial shouldn’t recognize the Confederate army. C’mon now.

And finally, DO: Remember that, regardless of the effort, a memorial will always be controversial.

These tiny memorials – typically only a couple of inches in area – are placed in front of former residences of Holocaust victims, frequently consisting of birth years, death years, and a brief summary of what happened to them. Also called “Stolpersteine,” these stones are spread across the continent in more than 1,200 cities. As of 2019, there are over 70,000 of them.

The idea of the Stolpersteine is that anyone going about their day can learn about someone who lost their life in the Holocaust, “stumbling” across them. They can be found in front of modern restaurants, shops, and apartment buildings. The everyday nature of these plaques isn’t for everyone, though; cities like Munich have banned them on public property, citing that it’s inappropriate for memorials recognizing victims of Nazi terror to be potentially stepped on. These sentiments are shared by the Jewish Cultural Center of Munich and Upper Bavaria and the Polish Institute of National Remembrance.

These contentious little stones speak to some but are offensive to others. While there is no objective response to the Stolpersteine, you’re welcome to cast your opinion; just know that there will always be someone who disagrees with you.

A good memorial creator recognizes that not everyone will agree with the nature of a memorial, but knows that public discussion is important.

Conclusion

A good memorial should be accessible both physically and intellectually. The creators of said memorial also need to recognize its political, cultural, and social roles and need to be direct and honest. Finally, freedom of speech and assembly need to be honored, because any memorial can be controversial.

And yet, to what extent do we even need memorials? An interesting perspective by Gary Younge, columnist for The Guardian:

“I think [statues of people] are poor as works of public art and poor as efforts at memorialization. Put more succinctly, they are lazy and ugly. So yes, take down the slave traders, imperial conquerors, colonial murderers, warmongers and genocidal exploiters. But while you’re at it, take down the freedom fighters, trade unionists, human rights champions and revolutionaries…They are among the most fundamentally conservative – with a small c – expressions of public art possible. They are erected with eternity in mind – a fixed point on the landscape. Never to be moved, removed, adapted or engaged with beyond popular reverence.”

While he specifically advocates for the removal of statues and not memorials as a whole, his ideas can be used to question how public space can be used to push an agenda. There’s no question that a memorial is inherently political – see any of the points made earlier. But now we can consider the economic and social aspects alongside this. Many public statues are paid for with taxpayer money – do we truly think that our money is going to the right place? Or what about the concept of representation: who is being memorialized and who is making the decisions?

Another opinion columnist, Sethembile Msezane, emphasizes that there are other ways to remember someone other than with a statue or memorial. We carry memories with us, and they are passed down from generation to generation. We also remember with performance and protest, vital aspects of who we are as humans.

But of course, there are significant counterclaims that also make sense. For example, maybe we keep problematic statues up because they show even the messy aspects of history that we can’t forget. Or there is the idea that statue removal can be a “slippery slope” that can lead to greater censorship. While I think that these arguments have merit, I can’t say definitively whether we need to tear down all memorials previously mentioned – but it doesn’t hurt to consider other perspectives. Whether in Europe or North America or Africa or Asia or South America, we are all inherently political, and so are our memories.

This article is dedicated to Dr. Steve Hoelscher, who introduced me to the idea of the politics of statues!

Categories: Culture

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-dmn.s3.amazonaws.com/public/4NJHLQSHGBMWPUGY3LHXDOM3TQ.jpg)